Hebron:

History & Overview

Hebron: Table of Contents | Tomb of the Patriarchs | Kiryat Arba

Hebron, located in the Judean hills south of Jerusalem, is the site of the oldest Jewish community in the world, dating back to Biblical times. Today, Hebron is home to some 250,000 Palestinians and approximately 700 Jews. An additional 6,000 Jews live in the adjacent community of Kiryat Arba.

Introduction

Hebron (Al-Khalil in Arabic) is located 32 kilometers south of Jerusalem and is built on several hills and wadis, most of which run north- to-south. The Hebrew word "Hebron" is explained as being derived from the Hebrew word for "friend" ("haver"), a description for the Patriarch Abraham. The Arabic "Al- Khalil," literally "the friend," has a nearly identical derivation and also refers to Abraham (Ibrahim), whom Muslims similarly describe as the friend of God. Hebron is one of the oldest continually occupied cities in the world, and has been a major focus of religious worship for over two millenia.Hebron has a long and rich Jewish history and is the site of the oldest Jewish community in the world. TheBook of Genesis relates that Abraham purchased the field where the Tomb of the Patriarchs is located as a burial place for his wife Sarah. According to Jewish tradition, the Patriarchs Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, as well the Matriarchs Sarah, Rebecca, and Leah are all buried in the Tomb.King David was anointed King of Israel in Hebron, and he reigned in the city for seven years. One thousand years later, during the first Jewish revolt against the Romans, the city was the scene of extensive fighting. Jews lived in Hebron continuously throughout the Byzantine, Arab, Mameluke and Ottoman periods and it was only in 1929 that the city became temporarily "free" of Jews as a result of a murderous Arab pogrom in which 67 Jews were murdered and the remainder forced to flee. After the 1967 Six-Day War, the Jewish community of Hebron was re-established.Today, Hebron has a mostly Sunni Muslim population and its Jewish community is comprised of roughly 700 people, including approximately 150 yeshiva students. An additional 6,650 Jews live in the adjacent community of Kiryat Arba.Hebron's climate has, since Biblical times, encouraged extensive agriculture and such areas surround the city. Farmers in the Hebron region usually cultivate fruits such as grapes and plums. In addition to agriculture, local economy relies on handicraft, small- and medium-scale industry and construction. Hebron is one of the most important marketplaces in the Palestinian Territories.

From Biblical Times to 1967

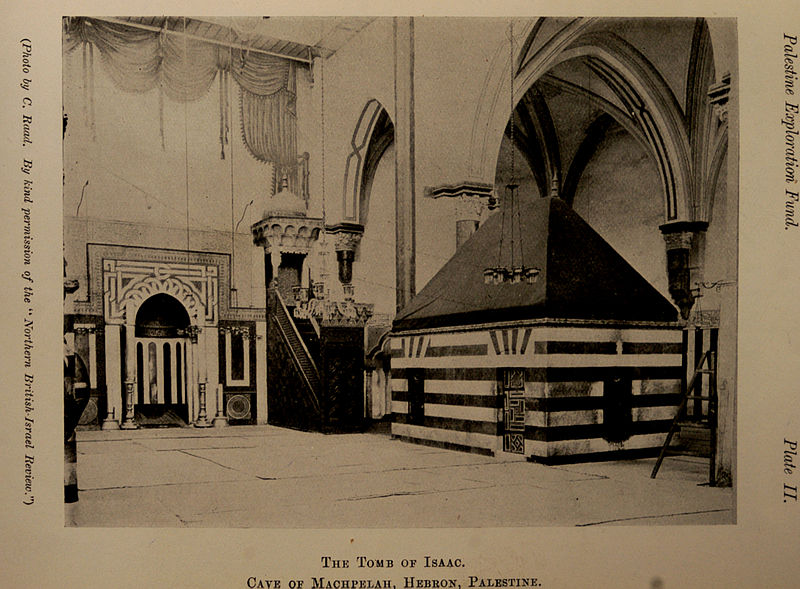

Numbers 13:22 states that (Canaanite) Hebron was founded seven years before the Egyptian town of Zoan, i.e. around 1720 BCE, and the ancient (Canaanite and Israelite) city of Hebron was situated at Tel Rumeida. The city's history has been inseparably linked with the Cave of Machpelah, which the Patriarch Abrahampurchased from Ephron the Hittite for 400 silver shekels (Genesis 23), as a family tomb. As recorded in Genesis, the Patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and the Matriarchs Sarah, Rebekah and Leah, are buried there, and — according to a Jewish tradition — Adam and Eve are also buried there.Hebron is mentioned 87 times in the Bible, and is the world's oldest Jewish community. Joshua assigned Hebron to Caleb from the tribe of Judah (Joshua 14:13-14), who subsequently led his tribe in conquering the city and its environs (Judges 1:1-20). As Joshua 14:15 notes, "the former name of Hebron was Kiryat Arba..."Following the death of King Saul, God instructed David to go to Hebron, where he was anointed King of Judah (II Samuel 2:1-4). A little more than 7.5 years later, David was anointed King over all Israel, in Hebron (II Samuel 5:1-3).The city was part of the united kingdom and — later — the southern Kingdom of Judah, until the latter fell to the Babylonians in 586 BCE. Despite the loss of Jewish independence, Jews continued to live in Hebron (Nehemiah 11:25), and the city was later incorporated into the (Jewish) Hasmonean kingdom by John Hyrcanus. King Herod (reigned 37-4 BCE) built the base of the present structure — the 12 meter high wall — over the Tomb the Patriarchs.The city was the scene of extensive fighting during the Jewish Revolt against the Romans (65-70, see Josephus4:529, 554), but Jews continued to live there after the Revolt, through the later Bar Kochba Revolt (132-135 CE), and into the Byzantine period. The remains of a synagogue from the Byzantine period have been excavated in the city, and the Byzantines built a large church over the Tomb of the Patriarchs, incorporating the pre- existing Herodian structure.Jews continued to live in Hebron after the city's conquest by the Arabs (in 638), whose generally tolerant rule was welcomed, especially after the often harsh Byzantine rule — although the Byzantines never forbade Jews from praying at the Tomb. The Arabs converted the Byzantine church at the Tomb the Patriarchs into a mosque.Upon capturing the city in 1100, the Crusaders expelled the Jewish community, and converted the mosque at the Tomb back into a church. The Jewish community was re-established following the Mamelukes' conquest of the city in 1260, and the Mamelukes reconverted the church at the Tomb of the Patriarchs back into a mosque. However, the restored Islamic (Mameluke) ascendancy was less tolerant than the pre-Crusader Islamic (Arab) regimes — a 1266 decree barred Jews (and Christians) from entering the Tomb of the Patriarchs, allowing them only to ascend to the fifth, later the seventh, step outside the eastern wall. The Jewish cemetery -- on a hill west of the Tomb — was first mentioned in a letter dated to 1290.The Ottoman Turks' conquest of the city in 1517 was marked by a violent pogrom which included many deaths, rapes, and the plundering of Jewish homes. The surviving Jews fled to Beirut and did not return until 1533. In 1540, Jewish exiles from Spain acquired the site of the "Court of the Jews" and built the Avraham Avinu ("Abraham Our Father") synagogue. (One year — according to local legend — when the requisite quorum for prayer was lacking, the Patriarch Abraham himself appeared to complete the quorum; hence, the name of the synagogue.)Despite the events of 1517, its general poverty and a devastating plague in 1619, the Hebron Jewish community grew. Throughout the Turkish period (1517-1917), groups of Jews from other parts of the Land of Israel, and the Diaspora, moved to Hebron from time to time, joining the existing community, and the city became a rabbinic center of note.In 1775, the Hebron Jewish community was rocked by a blood libel, in which Jews were falsely accused of murdering the son of a local sheikh. The community -- which was largely sustained by donations from abroad -- was made to pay a crushing fine, which further worsened its already shaky economic situation. Despite its poverty, the community managed, in 1807, to purchase a 5-dunam plot -- upon which the city's wholesale market stands today -- and after several years the sale was recognized by the Hebron Waqf. In 1811, 800 dunams of land were acquired to expand the cemetery. In 1817, the Jewish community numbered approximately 500, and by 1838, it had grown to 700, despite a pogrom which took place in 1834, during Mohammed Ali's rebellion against the Ottomans (1831-1840).In 1870, a wealthy Turkish Jew, Haim Yisrael Romano, moved to Hebron and purchased a plot of land upon which his family built a large residence and guest house, which came to be called Beit Romano. The building later housed a synagogue and served as a yeshiva, before it was seized by the Turks. During the Mandatory period, the building served the British administration as a police station, remand center, and court house.In 1893, the building later known as Beit Hadassah was built by the Hebron Jewish community as a clinic, and a second floor was added in 1909. The American Zionist Hadassah organization contributed the salaries of the clinic's medical staff, who served both the city's Jewish and Arab populations.During World War I, before the British occupation, the Jewish community suffered greatly under the wartime Turkish administration. Young men were forcibly conscripted into the Turkish army, overseas financial assistance was cut off, and the community was threatened by hunger and disease. However, with the establishment of the British administration in 1918, the community, reduced to 430 people, began to recover. In 1925, Rabbi Mordechai Epstein established a new yeshiva, and by 1929, the population had risen to 700 again.On August 23, 1929, local Arabs devastated the Jewish community by perpetrating a vicious, large-scale, organized, pogrom. According to the Encyclopedia Judaica:"The assault was well planned and its aim was well defined: the elimination of the Jewish settlement of Hebron. The rioters did not spare women, children, or the aged; the British gave passive assent. Sixty-seven were killed, 60 wounded, the community was destroyed, synagogues razed, and Torah scrolls burned."A total of 59 of the 67 victims were buried in a common grave in the Jewish cemetery (including 23 who had been murdered in one house alone, and then dismembered), and the surviving Jews fled to Jerusalem. (During the violence, Haj Issa el-Kourdieh -- a local Arab who lived in a house in the Jewish Quarter -- sheltered 33 Jews in his basement and protected them from the rioting mob.) However, in 1931, 31 Jewish families returned to Hebron and re-established the community. This effort was short-lived, and in April 1936, fearing another massacre, the British authorities evacuated the community.Following the creation of the State of Israel in 1948, and the invasion by Arab armies, Hebron was captured and occupied by the Jordanian Arab Legion. During the Jordanian occupation, which lasted until 1967, Jews were not permitted to live in the city, nor -- despite the Armistice Agreement -- to visit or pray at the Jewish holy sites in the city. Additionally, the Jordanian authorities and local residents undertook a systematic campaign to eliminate any evidence of the Jewish presence in the city. They razed the Jewish Quarter, desecrated the Jewish cemetery and built an animal pen on the ruins of the Avraham Avinu synagogue.

Reestablishing the Jewish Community

Israel returned to Hebron in 1967. The old Jewish Quarter had been destroyed and the cemetery was devastated. Since 1968, the re-established Jewish community in Hebron itself has been linked to the nearby community of Kiryat Arba. On April 4, 1968, a group of Jews registered at the Park Hotel in the city. The next day they announced that they had come to re- establish Hebron's Jewish community. The actions sparked a nationwide debate and drew support from across the political spectrum. After an initial period of deliberation, Prime Minister Levi Eshkol's Labor-led government decided to temporarily move the group into a near-by IDFcompound, while a new community -- to be called Kiryat Arba -- was built adjacent to Hebron. The first 105 housing units were ready in the autumn of 1972.In the decade following the Six Day War, when the euphoria of the victory had subsided, Judea and Samaria were still largely unsettled by Jews. Rabbi Moshe Levinger and a group of like-minded individuals determined that the time had come to return home to the newly liberated heartland of Eretz Yisrael.“As their first goal, the group decided to renew the Jewish presence in the the Jewish People’s most ancient city, Hebron. Word of the decision spread quickly and soon a nucleus of families was formed. Their objective: to spend Pesach in Hebron's Park Hotel. Hebron's Arab hotel owners had fallen on hard times. For years they had served the Jordanian aristocracy who would visit regularly to enjoy Hebron's cool dry air. The Six Day War forced the vacationers to change their travel plans. As a result, the Park Hotel's Arab owners were delighted to accept the cash-filled envelope which Rabbi Levinger placed on the front desk. In exchange, they agreed to rent the hotel to an unlimited amount of people for an unspecified period of time.“The morning of Erev Pesach, April, 1968 saw the Levinger family along with families from Israel's north, south and center packed their belongings for Hebron. They quickly cleaned and kashered the half of the hotel's kitchen allotted to them and began to settle in. Women and children slept three to a bed in the hotel rooms, while the men found sleeping space on the lobby floor. At least Ya'akov Avinu had a rock to place under his head, remembered one of the men in dismay.“Eighty-eight people celebrated Pesach Seder that night in the heart of Hebron. ‘We sensed that we had made an historical breakthrough", recalls Miriam Levinger, and we all felt deeply moved and excited.’”Today, Kiryat Arba has approximately 6,650 residents. Its built-up area comprises some 6,000 dunams, and is located about 750 meters from the Tomb at its nearest point. Kiryat Arba has its own elected local council, schools, religious and community institutions, clinics, and industrial/commercial zone. It draws its water from mains coming from the Etzion Bloc and the Herodion area to the north. About half of its residents work inJerusalem and its environs; 30% are employed in local education, health, and administrative services, and the remaining 20% are employed in local tourism, industry, and commerce. Hebron is also home to around 160,000 PalestiniansThe Jewish community in Hebron itself was re-established permanently in April 1979, when a group of Jews from Kiryat Arba moved into Beit Hadassah (see page 2 above). Following a deadly terrorist attack in May 1980 in which six Jews returning from prayers at the Tomb of the Patriarchs were murdered, and 20 wounded (see Annex I below), Prime Minister Menachem Begin's Likud-led government agreed to refurbish Beit Hadassah, and to permit Jews to move into the adjacent Beit Chason and Beit Schneerson, in the old Jewish Quarter. An additional floor was built on Beit Hadassah, and 11 families moved in during 1986.Since 1980, other Jewish properties and buildings in Hebron have been refurbished and rebuilt. Today the Hebron Jewish community comprises 19 families living in buildings adjacent to the Avraham Avinu courtyard (see page 2 above), the area also houses two kindergartens, the municipal committee offices, and a guesthouse; seven families living in mobile homes at Tel Rumeida; twelve families living in Beit Hadassah; six families living in Beit Schneerson; one family living in Beit Kastel; six families live in Beit Chason; Beit Romano, home to the Shavei Hevron yeshiva, is currently being refurbished.Local administration and services for the Hebron Jewish community are provided by the Hebron Municipal Committee, which was established by the Defense and Interior Ministries, and whose functions are similar to those of Israel's regular local councils. The Ministry of Housing and Construction has established the "Association for the Renewal of the Jewish Community in Hebron," to carry out projects in the city. The Association is funded both through the state budget and by private contributions. It deals with general development of, and for, the Jewish community.In addition to the Tomb of the Patriarchs, Tel Rumeida, the Jewish cemetery, and the historical residences mentioned above, other Jewish sites in Hebron include: 1) the Tomb of Ruth and Jesse (King David's father) which is located on a hillside overlooking the cemetery; 2) the site of the Terebinths of Mamre ("Alonei Mamre") from Genesis 18:1, where God appeared to Abraham, which is located about 400 meters from the Glass Junction (Herodian, Roman, and Byzantine remains mark the site today); 3) King David's Pool (also known as the Sultan's Pool), which is located about 200 meters south of the road to the entrance of the Tomb of the Patriarchs, which Jews hold to be the pool referred to in II Samuel 4:12, 4) the Tomb of Abner, Saul and David's general, which is located near the Tomb, and 5) the Tomb of Othniel Ben Kenaz, the first Judge of Israel (Judges 3:9-11).

Distinction Between "H1" & "H2"

Shuhada Street & the Old City

One main road runs through "H2" and connects the western to the eastern part of the city: Al-Shuhada Street. The traffic on this street, where three of the four Israeli settlements of Hebron are located, is tightly controlled by the IDF. Various restrictions are imposed on Palestinian motorists who want to use it. A bus station used to be located along Al-Shuhada Street. This popular meeting point was closed in 1986 and subsequently turned into an Israeli military compound. To this day, these successive measures have led to the virtual extinction of the economic activity along Al-Shuhada Street.In spite of being located inside the Israeli-controlled area of the city, the Souq situated inside the Qasba and behind Al-Shuhada Street remains one of the busiest in the West Bank. However, the wholesale vegetables market (Al-Hisbe), adjacent to the Souq, has also been closed by Israel, due to security considerations.The Qasba itself is no longer among the most densely populated areas of the city. Since the first half of the twentieth century, its population dropped from 8,000 to a few hundred. To reverse this evolution, the Palestinian local authorities have, since 1997, made a continuous effort to renovate, rehabilitate and develop the Old City. This led to an increase in the number of families moving into the Qasba. Similarly, efforts are being made to highlight its cultural heritage.Located northeast of the Old City, the Ibrahimi Mosque/Cave of Machpela is included in the area under Israeli control, as are Islamic institutions, and a number of old mosques.

Cave of Machpelah/Ibrahimi Mosque

The question of the Ibrahimi Mosque/Cave of Machpela is among the most sensitive issues in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. The sanctuary is dedicated to Abraham, the patriarch of both Arabs and Jews. Deep-rooted in Jewish tradition, the history of the Cave of Machpela takes on a special importance, as the site is believed to be the first piece of land bought by Abraham in the Promised Land.Since the Islamic conquest of the region, in the seventh century, the site is predominantly revered by Muslims as Al-Haram Al-Ibrahimi, the Abraham Sanctuary or Ibrahimi Mosque. For seven centuries, its access was restricted to Muslim worshippers only. Jewish pilgrims were allowed to pray at a special location, outside the building.During the 1967 War, on the same day the Israeli troops entered Hebron, the IDF chaplain placed a Torahscroll inside the Mosque. This initiative made it possible for Jews to hold prayers and religious services in various parts of the sanctuary - sometimes at the same time and place as the Muslims. This move raised a wide indignation among the Arab public opinion and Muslim clergymen. According to them, the installation of asynagogue inside the sanctuary challenges the Muslim character of the site.The recent history of the site was marked by the massacre of 29 Muslim worshippers by a Kiryat Arba settler, in February 1994. An Israeli commission headed by Meir Shamgar examined the circumstances of the bloodshed. Its recommendations led to a number of new arrangements, such as the establishment of a physical separation between the worshippers of the two communities and the tightening of the security checks at the entrances. It was also decided that on an equal number of days a year, the Ibrahimi Mosque/Cave of Machpela would be reserved for members of one community only.

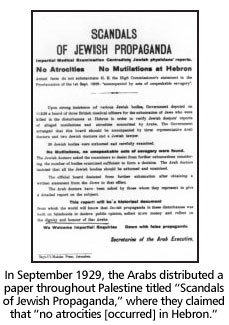

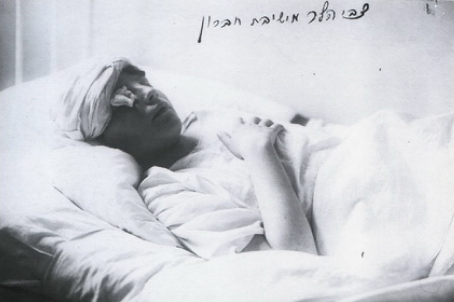

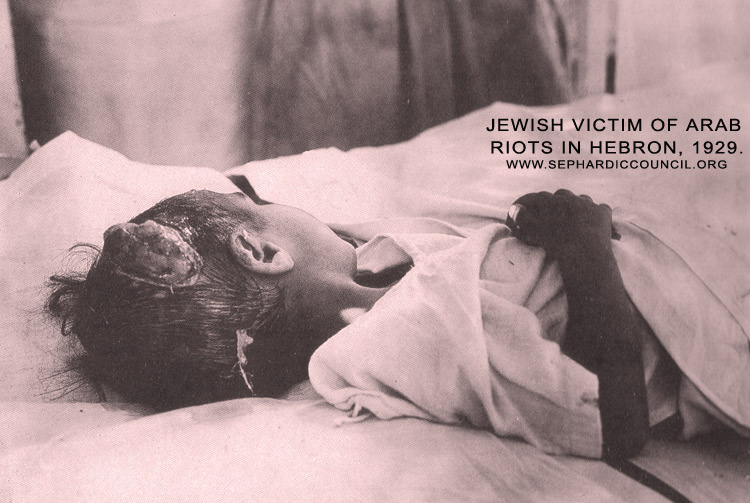

This Day in History: Aug 24, 1929: The Hebron massacre

The Hebron massacre refers to the killing of sixty-seven Jews (including 23 college students) on 24 August 1929 in Hebron, then part of Mandatory Palestine, by Arabs incited to violence by false rumors that Jews were massacring Arabs in Jerusalem and seizing control of Muslim holy places.[1] The event also left scores seriously wounded or maimed. Jewish homes were pillaged and synagogues were ransacked. Many of the 435 Jews who survived were hidden by local Arab families.[2][3] Soon after, all Hebron's Jews were evacuated by the British authorities.

Many returned in 1931, but almost all were evacuated at the outbreak of the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine. The massacre formed part of the 1929 Palestine riots, in which a total of 133 Jews were killed by Arabs, and brought the centuries-old Jewish presence in Hebron to an end.

The massacre, together with that of Jews in Safed, sent shock waves through Jewish communities in Palestine and around the world. It led to the re-organization and development of the Jewish paramilitary organization, the Haganah, which later became the nucleus of the Israel Defense Forces.[citation needed] In the metanarrative of Zionism, according to Michelle Campos, the event became 'a central symbol of Jewish persecution at the hands of bloodthirsty Arabs'[4] and was 'engraved in the national psyche of Israeli Jews', particularly those who settled in Hebron after 1967.[5]

Background

Simmering tensions

The city of Hebron holds special significance in Islam and Judaism, it being the site of theTomb of the Patriarchs. In 1929, the population numbered around 20,000, the majority of whom were Muslim Arabs. A small but significant community of around 700 Jews, a number living deep within Hebron but most renting houses from Arab proprietors on the outskirts,[6][7] also lived there. The Jewish community was divided between recent Ashkenazi immigrants and an older population of descendants of Sephardim who had inhabited the town for centuries. Ashkenazi Jews had been established in the town for at least a century.[8]

The two communities, Sephardim and Ashkenazi, maintained separate schools, worshipped in separate synagogues, and did not intermarry. The Sephardim were Arab-speakers, wore Arab-dress and were well-integrated, whereas many of the Ashkenazi community were yeshiva students who maintained 'foreign' ways, and had difficulties and misunderstandings with the Arab population.[9] Since the Balfour Declaration of 1917, tensions had been growing between the Arab and Jewish communities in Palestine.[10]The Muslim community of Hebron had a reputation for being highly conservative in religion. Though Jews had suffered numerous vexations in the past, and this hostility was to take an anti-Zionist turn after the Balfour Declaration.[11] generally, a peaceful relationship existed between both communities.[12]

In mid-August 1929, hundreds of Jewish nationalists marched to the Western Wall in Jerusalem shouting slogans such as The Wall is Ours and raising the Jewish national flag.[8] Rumours spread that Jewish youths had also attacked Arabs and had cursedMuhammad.[13][14] Following an inflammatory sermon the next day, hundreds of Muslims converged on the Western Wall, burning prayer books and injuring the beadle. The rioting soon spread to the Jewish commercial area of town[15][16] and the next day, a young Jew was stabbed to death.[17] The authorities failed to quell the violence. On Friday, August 23, inflamed by rumors that Jews were planning to attack al-Aqsa Mosque, Arabs started to attack Jews in the Old City of Jerusalem.

The first murders of the day took place when two or three Arabs passing by the Jewish Quarter of Mea Shearim were assassinated.[18] Rumours that Jews had massacred Arabs in Jerusalem arrived in Hebron by that evening.[6]

Haganah offers protection

Former Haganah member, Baruch Katinke, recalled that he had been informed by his superiors that 10-12 fighters were needed to protect the Jews in Hebron. On August 20, a group travelled to Hebron in the middle of the night and met with a Jewish community leader, Eliezer Dan Slonim. Katinke said that Slonim was adamant that no protection was needed as he was on good terms with the local Arabs and he trusted the a'yan (Arab notables) to protect the Jews. According to Katinke, Slonim postulated that the sight of the Haganah might instead cause a provocation. The group was soon discovered and Police Superintendent Raymond Cafferata ordered them to return to Jerusalem. Two others remained in Slonim's house, but the day after, they too returned to Jerusalem as requested by Slonim.[19]Hebron police force

Prelude

On Friday afternoon August 23, after hearing reports of rioting in Jerusalem, a crowd of 700 Arabs gathered at the city's central bus station intending to travel to Jerusalem. Cafferata attempted to placate them, and as a precaution, asked the British authorities to send reinforcements to Hebron.[8] He then arranged for a mounted patrol to be sent to the Jewish quarter, where he encountered Rabbi Yaakov Yosef Slonim-Dwek who asked for police protection after Jews had been attacked with stones. Cafferata instructed the Jews to stay in their homes, while he tried to disperse the crowds.[8] Jewish newspaper accounts carried various claims by survivors that they had heard Arab threats to "divvy up [Jewish] women", that Arab homeowners had told their Jewish neighbours "today will be the great slaughter," and that several of the victims took tea with so-called friends who, in the afternoon, became their killers.[21]

At around 4:00 pm, stones were thrown through the windows of Jewish homes. TheHebron Yeshiva was hit and as a student tried to escape the building, he was set upon by the mob who stabbed him to death. The sexton, the only other person in the building at the time, survived by hiding in a well. Some hours later Cafferata attempted to get the localmukhtars to assume responsibility for law and order, but they told him that the Mufti had told them to take action or be fined due to the 'Jewish slaughter of Arabs' in Jerusalem. Cafferata told them to return to their villages, but expecting some disturbances, he slept in his office that night.[8]

The attack

The rampage and the killing

At about 8.30 am Saturday morning, the first attacks began to be launched against houses were Jews resided,[6] after a crowd of Arabs armed with staves, axes and knives appeared in the streets. The first location to be attacked was a large Jewish house on the main road. Two young boys were immediately killed, whereupon the mob entered the house and beat or stabbed the other occupants to death.

Cafferata appeared on the scene, gave orders to his constables to fire on the crowd and personally shot dead two of the attacking Arabs.[6] While some dispersed, the rest managed to break through the pickets, shouting "on to the ghetto!" Requested reinforcements had not arrived in time. This later became the source of considerable acrimony.[8]

According to a survivor, Aharon Reuven Bernzweig, "right after eight o'clock in the morning we heard screams. Arabs had begun breaking into Jewish homes. The screams pierced the heart of the heavens. We didn't know what to do… They were going from door to door, slaughtering everyone who was inside. The screams and the moans were terrible. People were crying Help! Help! But what could we do?"

Soon after news of the first victim had spread, forty people assembled in the house of Eliezer Dan Slonim. Slonim, the son of the Rabbi of Hebron, was a member on the city council and a director of the Anglo-Palestine Bank. He had excellent relations with the British and the Arabs and those seeking refuge with him were confident they would come to no harm. When the mob approached his door, they offered to spare the Sephardicommunity if he would hand over all the Ashkenazi yeshiva students. He refused, saying "we are all one people," whereupon he was shot dead along with his wife and 4-year-old son.[22] From the contemporary Hebrew press it appears that the rioters targeted the Zionist community for their massacre. Four-fifths of the victims were Ashkenazi Jews, though some had deep roots in the town, yet a dozen Jews of eastern origin, Sephardim and Maghrebi, were also killed.[21] Ben-Zion Gershon, for example, the Beit Hadassah Clinic pharmacist, a cripple who had served both Jews and Arabs for 4 decades, was killed together with his family: his daughter was raped and then murdered, and his wife's hands were cut off.[8]

Account of Raymond Cafferata

After the masacre, Cafferata testified:

"On hearing screams in a room, I went up a sort of tunnel passage and saw an Arab in the act of cutting off a child's head with a sword. He had already hit him and was having another cut, but on seeing me he tried to aim the stroke at me, but missed; he was practically on the muzzle of my rifle. I shot him low in the groin. Behind him was a Jewish woman smothered in blood with a man I recognized as a[n Arab] police constable named Issa Sheriff from Jaffa. He was standing over the woman with a dagger in his hand. He saw me and bolted into a room close by and tried to shut me out-shouting in Arabic, "Your Honor, I am a policeman." ... I got into the room and shot him."[8][23][24]

Account of Jacob Joseph Slonim

Rabbi Jacob Joseph Slonim, the Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Hebron, stated that after his Arab acquaintances had informed him that local hooligans intended to attack the talmudical academy, he had gone to ask for protection from District Officer Abdullah Kardus, but was denied an audience with him. Later on after being attacked in the street, he had approached the chief of police, but Cafferata refused to take any measures, telling him that "the Jews deserve it, you are the cause of all troubles." The next morning, Slonim again urged the District Officer to take preventative measures, but he was told there was "no ground for fear. A great number of police is available. Go and reassure the Jewish population." Two hours later, a mob incited by speeches started breaking into Jewish homes with cries of "Kill the Jews." The massacre lasted an hour and a half, and only after it had died down, did the police take action, firing shots into the air, whereupon the crowds immediately dispersed. Sloinm himself was saved by a friendly Arab.[25] Of the 67 victims of the massacre, 12 were women and 3 were children under the age of 5.[6]Looting, destruction and desecration

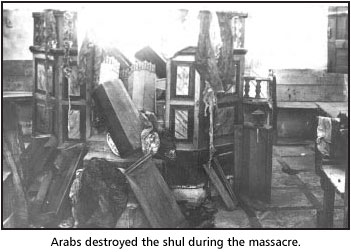

The attack was accompanied by wanton destruction and looting. A Jewish hospital, which had provided treatment for Arabs, was attacked and ransacked. Numerous Jewish synagogues were vandalised and desecrated.[26] According to one account, Torah scrolls in casings of silver and gold were looted from the synagogues and manuscripts of great antiquity were pilfered from the library of Rabbi Judah Bibas.[27] The library, founded in 1852, was partly burned and destroyed.[28] In one instance, a rabbi who had saved a Torah scroll from a blazing synagogue, later died from his burns.[29]

Arabs shelter Jews

Around 25 Arab families helped save 280-300 Jews by sheltering them during the melee.[2]Aharon Reuven Bernzweig related that an Arab named Haj Eissa El Kourdieh, saved a group of 33 Jews after he insisted they hide in his cellar. There they waited with a "deadly fear" for the trouble to pass, worrying that the "murderers outside would hear [the little children who kept crying]." From the cellar, they heard cries of "today is a day that is holy to Mohammed. Anyone who does not kill Jews is a sinner." Meanwhile, several Arab women, stood guard outside, repetitively challenging the claims of the screaming mob that they were sheltering Jews.[2] Yonah Molchadsky gave birth while taking refuge in an Arab basement. Molchadsky later related that when the mob demanded that Arabs give up any Jews they were hiding, her host told them "we have already killed our Jews," whereupon the mob departed.[30] The family of Abu Id Zaitoun rescued Zmira Mani and other Jews by hiding them in their cellar and protecting them with their swords. They later found policeman to escort them safely to the police station at Beit Romano.[31]

Survivors

Around 435 Jews survived, most having been saved by a handful of Arab families. Around 130 saved themselves by hiding or by taking refuge in the British police station at Beit Romano on the outskirts of the city.[2] After order had been restored, all the Jews were gathered at the police station where hundreds of people were confined for three days, without food or water. They were also forbidden from making telephone calls. All the survivors were then evacuated to Jerusalem.

Aftermath

Numbers killed and injured

In total, 67 Jews and 9 Arabs were killed.[32] Of the Jews killed, 59 died during the rioting and 8 more later succumbed to their wounds. They included a dozen women and three children under the age of three. Twenty-four of the victims were students from the Hebron yeshiva, seven of whom were American or Canadian. The bodies of 57 Jewish victims were buried in mass graves by Arabs, without regard to Jewish burial ritual. Most of the murdered Jews were of Ashkenazi descent, while 12 were Sephardi. 58 are thought to have been injured, including many women and children. One estimate put the figure at 49 seriously and 17 slightly wounded.[2] A letter from the Jews of Hebron to the High Commissioner described cases of torture, mutilation and rape.[33] Eighteen days after the massacre, the Jewish leadership requested that bodies be exhumed to ascertain whether deliberate mutilation had taken place.[34] But after 20 bodies had been disinterred and reburied, it was decided to discontinue. The bodies had been exposed for two days before burial and it was almost impossible to ascertain whether or not they had been subject to mutilations after or during the massacre.[35] No conclusions could therefore be made.[36]

Reaction and response

Commission of Enquiry

The Shaw Commission was a British enquiry that investigated the violent rioting in Palestine in late August 1929. It described the massacre at Hebron:

"About 9 o'clock on the morning of the 24th of August, Arabs in Hebron made a most ferocious attack on the Jewish ghetto and on isolated Jewish houses lying outside the crowded quarters of the town. More than 60 Jews – including many women and children – were murdered and more than 50 were wounded. This savage attack, of which no condemnation could be too severe, was accompanied by wanton destruction and looting. Jewish synagogues were desecrated, a Jewish hospital, which had provided treatment for Arabs, was attacked and ransacked, and only the exceptional personal courage displayed by Mr. Cafferata – the one British Police Officer in the town – prevented the outbreak from developing into a general massacre of the Jews in Hebron."[26]

Cafferata testified to the Commission of Enquiry in Jerusalem on 7 November. The Timesreported Cafferata's evidence to the Commission that "until the arrival of British police it was impossible to do more than keep the living Jews in the hospital safe and the streets clear [because he] was the only British officer or man in Hebron, a town of 20,000".[37]

On September 1, Sir John Chancellor condemned:-

'the atrocious acts committed by bodies of ruthless and bloodthirsty evildoers... murders perpetrated upon defenceless members of the Jewish population... accompanied by acts of unspeakable savagery.'

Trials and convictions

One of the chief instigators of the massacre, Sheik Taleb Markah, denied the allegations against him and claimed he endeavoured to pacify the mob.[38] He was sentenced to two years imprisonment.[39] Two of the four Arabs charged with the murder of 24 Jews in the house of Rabbi Jacob Slonim were sentenced to death.[40]

In Palestine overall, 195 Arabs and 34 Jews were sentenced by the courts for crimes related to the 1929 riots. Death sentences were handed down to 17 Arabs and two Jews, but these were later commuted to long prison terms except in the case of three Arabs who were hanged.[41] Large fines were imposed on 22 Arab villages or urban neighborhoods.[41] The fine imposed on Hebron was 14,000 pounds.[42] Financial compensation totaling about 200,000 pounds was paid to persons who lost family members or property.[41]

Decline of Jewish community

Some Hebron Arabs, amongst whom the President of Hebron's Chamber of Commerce, Ahmad Rashid al-Hirbawi, favoured the return of Jews to the town.[43] The returning Jews quarrelled with the Jewish Agency over funding. The Agency did not agree to the idea of reconstituting a mixed community, but rather pressed for the establishment of a Jewish fortress wholly distinct from the Arab quarters of Hebron.[44] In the spring of 1931, 160 Jews returned together with Rabbi Chaim Bagaio. During the disturbances of 1936 they all left the town for good, except for one family, that of Yaakov Ben Shalomn Ezra, an eighth generation Hebronite who was a dairyman, who eventually left in 1947, on the eve of the1948 Palestine War.[45]

Yeshiva relocates to Jerusalem

After the massacre, the remainder of the Hebron yeshiva relocated to Jerusalem.[8]

Jewish re-settlement after 1967

During the 1967 Six-Day War, Israel gained Hebron from Jordan. Residents, terrified that Israeli soldiers might massacre them in retaliation for the events of 1929, waved white flags from their homes and voluntarily turned in their weapons.[46] Subsequently, Israelis settled in Hebron as part of Israel's settlement program, and the Committee of The Jewish Community of Hebron was established. Today, hundreds of Israelis live in Hebron, and thousands live in Kiryat Arba, an Israeli settlement established on the city's outskirts.

Descendants of the survivors are divided, with some claiming they wish to return, but only when Arab and Jewish residents can find a way to live together peacefully. Other survivors and descendants of survivors support the new Jewish community in Hebron.[47]

1999 DOCUMENTARY FILM

Noit Gevas, daughter of a survivor, discovered that her grandmother, Zemira Mani (who was the granddaughter of Hebron's chief Sephardic rabbi, Eliyahu Mani), had written an account of the massacre, published in the Haaretz newspaper in 1929. In 1999 Gevas released a film containing testimonies of 13 survivors that she and her husband Dan had managed to track down from the list in "Sefer Hebron" ("The Book of Hebron"). Originally intended to document the story of the Arab who had saved Gevas's mother from other Arabs, it became also an account of the atrocities of the massacre itself. These survivors (most of whom no longer live in Israel) are mixed as to whether they can forgive.

In the film, "What I Saw in Hebron"[48] the survivors – now very elderly – describe pre-massacre Hebron as a kind of paradise surrounded by vineyards, where Sephardic Jews and Arabs lived in idyllic coexistence. The well-established Ashkenazi residents were also treated well – but the Arabs' anger was roused by followers of the Jerusalem Mufti as well as local chapters of the (Arab) Muslim-Christian Societies.

According to Asher Meshorer (Zemira Mani's son and Noit Geva's father), his aunt (Zemira Mani's sister - who was not present in Hebron during the massacre) had told him that the Arabs from the villages essentially wanted to kill only the new Ashkenazim. According to her, there was an alienated Jewish community that wore streimels, unlike the Sephardi community, which was deeply rooted, speaking Arabic and dressing like Arab residents.

When the riots started, representatives of the Arabs came to the chief Hebron Rabbi, Rabbi Slonim Dwek, with a proposal – if he allowed them to kill 70 students from the yeshiva in Hebron, they would not kill the other Ashkenazim or the Sephardim. Rabbi Slonim Dwek told them, "We Jews are all one people." He was the first person to be killed in the riots, as he held his eldest son, 4 years old in his hands, who was also killed.[49]

The Mani family was saved by an Arab neighbour, Abu 'Id Zeitun, who was accompanied by his brother and son. Nowadays (in 1999), according to Abu 'Id Zeitun, the house in which the Jews were hidden – his father's house – had been confiscated by the IDF, and today it houses a kindergarten for the settlers.[citation needed]

Taken from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1929_Hebron_massacre [23.08.2013]

References

3. ^ Independent 26 January 2008 A rough guide to Hebron: The world's strangest guided tour highlights the abuse of Palestinians

4. ^ Michelle Campos, 'Remembering Jewish-Arab Contact and Conflict,' in Sandra Marlene Sufian, Mark LeVine, (eds.)Reapproaching Borders: New Perspectives on the Study of Israel-Palestine, Rowman & Littlefield 2007 p. 41 of pp. 41-65.

5. ^ Matthew Levitt Negotiating Under Fire: Preserving Peace Talks in the Face of Terror Attacks, Rowman & LIttlefield, 2008 p. 28

7. ^ Segev, Tom (2000) p. 318...A few dozen Jews lived deep within Hebron, in a kind of ghetto where there were also several synagogues. But the majority lived on the outskirts, along the roads to Be'ersheba and Jerusalem, renting homes owned by Arabs, a number of which were built for the express purpose of housing Jewish tenants.

8. ^ a b c d e f g h i Segev, Tom (2000). One Palestine, Complete. Metropolitan Books. pp. 314–327. ISBN 0-8050-4848-0.

9. ^ Michelle Campos, 'Remembering Jewish-Arab Contact and Conflict,' in Sandra Marlene Sufian, Mark LeVine, (eds.)Reapproaching Borders: New Perspectives on the Study of Israel-Palestine, Rowman & Littlefield 2007 pp.41-65 pp.55-56.

12. ^ 'Hebron had, until this time, been outwardly peaceful, although tension hid below the surface. The Sephardi Jewish community in Hebron had lived quietly with its Arab neighbors for centuries.' Shira Schoenberg ‘The Hebron Massacre of 1929,’ Jewish Virtual Library

15. ^ Report of the Commission on the Palestine Disturbances of August 1929, Command paper Cmd. 3530

16. ^ Gilbert, Martin (1977). "Jerusalem, Zionism and the Arab Revolt 1920-1940". Jerusalem Illustrated History Atlas.London: Board of Deputies of British Jews. p. 79. ISBN 0-905648-04-8.

17. ^ J.Bowyer Bell, Terror out of Zion: The Fight for Israeli Independence, Transaction ed.Prologue p.1 name

19. ^ Baruch Katinke (1961). מאז ועד הנה [From then until now] (in Hebrew). קרית ספר. p. 271. Retrieved 1 June 2011. andtestimony in the Haganah archives

21. ^ a b Michelle Campos, 'Remembering Jewish-Arab Contact and Conflict,' in Sandra Marlene Sufian, Mark LeVine, (eds.)Reapproaching Borders: New Perspectives on the Study of Israel-Palestine, Rowman & Littlefield 2007 pp.41-65, pp55-56

24. ^ It should be noted that some survivors testified that more than one of the Hebronite Arab policemen joined the riot.[citation needed]

26. ^ a b "Commission on the Palestine Disturbances of August 1929 (The Shaw Commission)". March 1930. p. 64.

30. ^ Haaretz. Survivor of 1929 Hebron Massacre recounts her ordeal by Eli Ashkenazi. Last accessed: 12 August 2009/

31. ^ Zmira Mani (later renamed Zmira Meshorer), "What I saw in Hebron" ("ma shera'iti beħevron"), Haaretz, Sep 12, 1929, reprinted in: Knaz, Yehoshua (ed.) (1996).Haaretz - the 75th Year, Schocken Publishing, Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, pp. 33–34 (in Hebrew).

36. ^ Tom Segev (2000) p. 330. The Department of Health report to the Shaw Commission said: "A complete post mortem record of the cause of death in the case of the killed was not obtainable at the time, in view of the large number of wounded that had to be dealt with by the limited medical staff. As a result of external inspection by the Senior Medical Officer and British Police Officer no mutilation of bodies was observed. A subsequent exhumation demanded by the Jewish authorities with the object of proving or disproving deliberate mutilation took place on September 11th. Twenty bodies were exhumed and examined by a specially appointed Committee consisting of the Government Pathologist, Dr. G. Stuart, and two non-official British doctors, Dr. Orr Ewing and Dr. Strathearn. The representatives of the Jewish authorities asked that the remaining bodies not be exhumed. The alleged mutilation of bodies was not confirmed by the Committee." Minutes of Evidence, Exhibit 17 (page 1031).

37. ^ 'The Hebron Tragedy. Mr. Cafferata's Evidence', From Our Correspondent. The Times, Friday, November 8, 1929; pg. 13; Issue 45355; col D.

41. ^ a b c Report by his Majesty's Government...to the Council of the League of Nations on the Administration of Palestine and Trans-Jordan for the year 1930. Sections 9–13.

43. ^ The New Republic. 'The Tangled Truth', by Benny Morris, May 07, 2008, book review of Hillel Cohen's (2008) Army of Shadows: Palestinian Collaboration with Zionism, 1917-1948 Translated by Haim Watzman University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-25221-7

44. ^ Michelle Campos, 'Remembering Jewish-Arab Contact and Conflict,' in Sandra Marlene Sufian, Mark LeVine, (eds.)Reapproaching Borders: New Perspectives on the Study of Israel-Palestine, Rowman & Littlefield 2007 pp. 41-65 p. 56.

48. ^ "What I Saw in Hebron", The National Center for Jewish Film, Israel, 1999, 73 min, color, Hebrew & Arabic w/ English subtitles. Verified 27 Apr 2008.

49. ^ Hebron Diary, daughter of a survivor tells story of film "Things I saw in Hebron". Verified 27 Apr. 2008.

No comments:

Post a Comment