Explosion at the King David Hotel

|

Shortly after noon on Monday July 22nd, 1946, a battered delivery truck was driven into the side entrance of the King David Hotel, just west of the old city of Jerusalem and headquarters of both Palestine's civil administration and the British army in Palestine and Transjordan. Eight armed men dressed as Arab workers then forced their way into the hotel's service bay. After overpowering and locking up the chief delivery clerk and the kitchen staff, they unloaded seven milk churns packed with 350 kilograms of TNT and gelignite from the truck and dragged them one by one along a long and narrow corridor to La Regence, the hotel's basement bar directly underneath the civilian and the military headquarters in the south wing. As they did so, they were challenged by a British army officer, whom they shot and fatally injured. While some of the fake Arab workers acted as lookouts, others placed the milk churns next to two supporting columns in the basement bar and ignited their thirty-minute fuses.As they made their getaway, the attackers attracted the attention of British army sentries alerted by the unusual commotion in the basement. A gun battle ensued, in which two of the intruders were wounded, one of them seriously. Hearing shots, people peering out of the hotel windows caught glimpses of men they thought were Arabs running away. Shortly afterwards, a bomb exploded in the street outside the hotel, wounding the passengers in a passing Arab bus. The shooting and now the bombing encouraged people inside the hotel to stay where they were. Although a woman claiming to speaking on behalf of the Hebrew Underground had telephoned a warning to The Palestine Post newspaper and the French Consulate about a bomb in the King David, very few people there realized the danger they now faced.

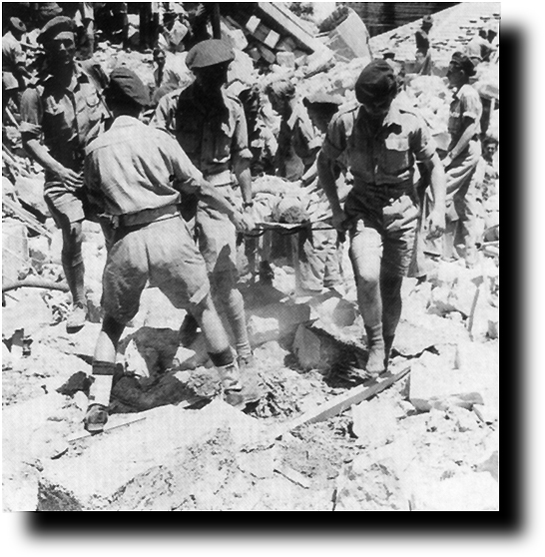

At 12.37pm, a massive explosion tore apart the hotel's south wing, hurling big fragments of steel, concrete, sandstone masonry and human body parts into nearby buildings. The lethal shower of debris also engulfed policemen and onlookers who had gathered at the scene of the earlier bombing, killing and injuring scores more people. Working frantically in blazing heat over the next seventy-two hours, rescue workers managed to pull six badly injured survivors from the wreckage but ninety-one people - Britons, Arabs and Jews - had perished in the blast.

The bombing of the King David Hotel was as shocking to contemporaries in 1946 as the destruction of the World Trade Center in 2001. British prime minister Clement Attlee declared in the House of Commons, 'On July 22nd, one of the most dastardly and cowardly crimes in recorded history took place'. The Jewish Agency, the body officially recognized by the British as representing Palestine's 450,000 Jews, expressed its 'feelings of horror at the base and unparalleled act perpetrated today by a gang of criminals'.

The 'gang of criminals' responsible for bombing the King David Hotel was a Jewish underground group known as 'The National Military Organisation' or, in Hebrew, Irgun Zwei Leumi. Its leader was a thirty-three-year-old Polish Jew called Menachem Begin, for whose capture the British had posted a #2,000 reward, dead or alive. Just as Osama bin Laden is a hero for fundamentalist Islamists today, Begin was seen by many Jews in Palestine and in the Jewish Diaspora as a fearless freedom fighter combating an alien tyranny. In his autobiography, A Tale of Love and Darkness (2004) Israeli author Amos Oz remembered him as his childhood idol:

In my mind, I saw his form swathed in clouds of biblical glory. I imagined him in his secret headquarters in the wild ravines of the Judaean Desert, barefoot, with a leather girdle, flashing sparks like the prophet Elijah among the rocks of Mount Carmel.

In reality, Begin, living under an assumed name in a poor suburb of Tel-Aviv, led a hunted existence. Unlike Sinn Fein's Michael Collins, he never led his men into battle but his young fighters looked up to him with unqualified admiration and respect. Under his leadership, the Irgun suffered no splits, no attempts to topple him. Begin was also the movement's chief ideologue and propagandist. In clandestine radio broadcasts and in dramatic posters featuring the Irgun symbol - a hand clenching a rifle superimposed on a map of Palestine and Transjordan inscribed with the Hebrew name for the land of Israel - came a ringing call to arms: 'By fire and blood, Judea fell. By fire and blood, Judea will rise once again!' For 2,000 years, the Jewish people had known only exile and despair; the time to recreate the Jewish nation was near. But first, the 'Nazi-British' occupier had to go.

In 1946, most Britons in Palestine would have gladly obliged, convinced that none of its inhabitants wanted them to stay. Suspicious of British intentions ever since the 1917 Balfour Declaration and its contradictory set of promises to both peoples in Palestine, the Arabs had been the first to rise up in revolt. To break their rebellion, the colonial authorities introduced a host of repressive measures - manhunts, collective punishments, administrative detentions, military courts and hangings. Officials who had served in Ireland during the war against Sinn Fein in 1920-21 now saw worrying similarities in Palestine. 'I remember you predicted this all some years ago... if the Colonial Office did not alter its policy, you said we shall have another Ireland. We have one, and so bad has this second Ireland now become that we must deal with it as we did with the other,' wrote a colonial officer to a former High Commissioner for Palestine, John Chancellor. By that, he meant creating two states in Palestine, one for the Arabs and one for the Jews, just as in 1922 Ireland had been partitioned when it became impossible to reconcile Protestant Unionism with Irish nationalism. However, the Arabs rejected any idea of sharing their homeland with foreigners. The Arab uprising lasted nearly three years, from 1936 to 1939, tying down the bulk of Britain's small professional army in a wearisome and brutal counter-insurgency campaign. During the conflict 153 British lives were lost; 961 Jews and Arabs were killed in guerrilla ambushes and assassinations, while 2,000 rebels died in skirmishes with the army and police and a further 112 were hanged.

With war in Europe looming in the calculations of diplomats and military strategists in Whitehall, the British dared not relinquish such strategic assets as the Suez Canal and the oil fields of the Middle East. They now deliberated the pros and cons of offering continued support for the Zionist cause against the need to secure the support - or at least the acquiescence - of Arab states in the Middle East for the British cause, and came down in favour of the latter. 'If we must offend one side,' Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain cynically commented, 'let us offend the Jews rather than the Arabs'. The White Paper of May 1939, issued just as the Arab revolt was petering out, set out the new British policy for Palestine: Jewish immigration was to be strictly limited, land sales to Jews severely curtailed, and at the end of ten years an independent Palestine where Jews and Arabs would share power would be established.

The White Paper outraged Zionists everywhere, but the mainstream movement, led inside Palestine by David Ben-Gurion and represented worldwide by Zionism's elder statesman, Chaim Weizmann, was not yet prepared to abandon the British. The cause still had powerful friends in London and one of them was Winston Churchill, whom Weizmann counted as a personal friend and a Zionist supporter since the British had been given the Mandate to administer Palestine by the League of Nations in June 1922, when Churchill had been Colonial Secretary. As Minister of Defence as well as prime minister from May 1940, Churchill maintained a firm grip on strategic decision-making but he would not challenge policies already agreed by the rest of the Cabinet, even those he personally disliked. Putting his reservations over British policy towards Palestine to one side, he got on with the business of fighting Hitler, leaving the mainstream Zionist movement little choice but, as Ben-Gurion put it, 'to fight the war against Hitler as if there was no White Paper and to fight the White Paper as if there was no war.'

However, radical elements in the Yishuv, Palestine's Jewish community, were already at war with the British. They belonged to the Irgun Zwei Leumi, the military wing of the Revisionist Zionist movement established in 1931 and led by the charismatic Zionist ideologue Ze'ev Jabotinsky. Jabotinsky had broken away from the mainstream movement in 1925, angry at what he regarded as obstructions to the creation of a strong Jewish homeland stretching from the Nile to the Euphrates placed by pusillanimous Jewish leaders, untrustworthy British colonial administrators and treacherous Arabs. His fiery oratory attracted a significant following in the Yishuv's 'unaffiliated community', people who did not belong to the kibbutz movement, the Histradut trade union or any of the mainstream Zionist cultural organizations. It also won him great popularity in Eastern Europe, especially among religious Jews for whom the secular ethos of Ben-Gurion's Zionism was anathema. One of Jabotinsky's Eastern European disciples was Menachem Begin, a Polish law student born in Brest-Litovsk in 1913.

The Irgun saw itself as the avenging sword of the Yishuv. A young romantic poet with a taste for violence called Avraham Stern was one of its leading activists. During the Arab Revolt, its members responded to attacks on Jews by bombing Arab coffee houses, street markets and the entrances to mosques, killing and maiming scores of people. They rarely issued warnings. Following the May 1939 White Paper, the Irgun directed its weapons against the Mandate but, after the outbreak of war in September, it declared a truce, promising co-operation with the British against the common enemy, Nazi Germany. Stern quit the organization in disgust and continued his war with a small but dedicated band of followers called the Fighters for the Freedom of Israel - in Hebrew, Lohamei Herut Yisrael or Lehi. The British found it easier to call them the Stern Gang.

Begin reached his Promised Land in May 1942, in the uniform of General Anders' Polish army, after the grimmest of odysseys - flight from Nazi occupation, arrest and interrogation by Stalin's secret police and incarceration in a Siberian Gulag. His arrival in Palestine coincided with a period of disarray for the Revisionist movement. Jabotinsky had died in exile in August 1940. Months later, another key figure, the Irgun commander David Raziel, was killed while on a clandestine mission for the British in Iraq. Lehi was even worse off; in February 1942, Avraham Stern was shot dead by a British police officer, allegedly while resisting arrest, and many of his comrades ended up behind bars. Begin shed his Polish army battledress and became the Irgun's commander-in-chief.

In the summer of 1942, with Rommel's Afrika Korps just eighty miles from Alexandria, the whole of the Yishuv trembled at the prospect of an imminent Nazi invasion but, with Montgomery's victory at El Alamein in November, the threat receded. Jewish anger was once more directed at the British for their refusal to allow large numbers of Jews fleeing Nazi-occupied Europe to enter Palestine. On February 1st, 1944, the Irgun declared war on the British Mandate. Begin's 'boys' attacked British outposts responsible for monitoring the traffic of illegal Jewish immigrants and then turned to robbing banks, bombing government buildings and assassinating police officers. Lehi, which had never abandoned its war against the British, went after bigger fry. In Cairo on November 5th, 1944, two young Lehi gunmen shot dead one of Churchill's closest friends, Lord Moyne who was the British Minister of State for the Middle East. His murder made the British premier waver in his support for the Zionist cause. In the House of Commons a fortnight later, Churchill warned the mainstream Zionist movement:

If there is to be any hope of a peaceful and successful future for Zionism, these wicked activities must cease and those responsible for them must be destroyed, root and branch.

The Jewish Agency took Churchill's warning to heart and sent its own underground militia, the Haganah, after the Irgun and Lehi 'dissidents'. During the 'hunting season', as it became known, dozens of 'dissidents' were rounded up, imprisoned and tortured. Many were turned over to the British. But Begin refused to fight back, believing nothing could harm the Jewish liberation struggle more than a civil war. 'The season' was still in full force when on May 8th, 1945, the war in Europe ended. Palestine's 450,000 Jews now learnt about the slaughter of millions of their brethren in Europe. This included all of Begin's family in Poland. Amid the anguish, attention focused on bringing to Palestine the 250,000 homeless survivors of Nazi genocide now languishing in Allied camps for displaced persons in Germany and Austria.

Nevertheless, the mainstream Zionists believed that, with the war's victorious conclusion, British policy towards Palestine would shift decisively in their favour. In July 1945, the Labour Party led by Clement Attlee won a decisive victory over Churchill in the British general election. For years, the annual Labour Party conferences had voted in favour of a Jewish state in Palestine, even recommending the transfer of Arabs from Jewish territory in any partition plan. The Zionist movement expected that the new British government would move quickly to scrap the 1939 White Paper but its Foreign Secretary, Ernest Bevin, did no such thing. Surveying Great Britain's bleak post-war economic outlook and the first signs of a Cold War with the Soviet Union, he quickly concluded that the British still could not afford to surrender control over the Suez Canal or the Middle Eastern oil fields. Therefore, a substantial British garrison would stay in Palestine and strict limits on Jewish immigration would remain.

If the 1939 White Paper had mortally wounded the Balfour Declaration and its promise to secure the establishment of a Jewish homeland, Bevin killed it stone dead in 1945. The whole Zionist movement now saw itself at war with Great Britain. In the United States, it waged a highly effective propaganda campaign vilifying Bevin for single-handedly barring the way to Palestine for the Holocaust survivors in the displaced person camps. Simultaneously, the Haganah sent shiploads of Jewish refugees across the Mediterranean to Palestine in defiance of the Royal Navy. Their imprisonment in detention camps on Cyprus did as much damage to Britain's reputation as Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay have done to the current US administration. Inside Palestine itself, 'the season' was called off and the Haganah combined with the Irgun and Lehi - the so-called 'dissident forces' - to form the 'United Jewish Resistance'. From October 1945 to June 1946, Jewish resistance fighters attacked government buildings, army bases, police stations, airfields, roads and railways, killing eighteen British soldiers, wounding another 101 and inflicting similar losses on the Palestine police. To quell the disorder, the Mandate authorities resurrected the same emergency regulations used to defeat the Arab revolt of the late thirties; their severity astounded the Labour MP Dick Crossman who wrote in his diary during a visit in March 1946: 'There can be no doubt that Palestine today is a police state'. Nevertheless, he wondered just who was in charge, observing:

The Jewish Agency ... is a state within a state, with its own budget, secret cabinet, army, and above all intelligence service. It is the most efficient, dynamic, toughest organization I have ever seen and it is not particularly afraid of us.

The British High Commissioner, Sir Alan Cunningham, hoping that 'moderates' in the Jewish Agency could be persuaded to restrain the 'hotheads', had banned the imposition of collective fines and the demolition of homes in Jewish districts where British soldiers and police had been attacked. To many army and police commanders, Cunningham's restraint was a sign of weakness. At the insistence of Field Marshal Montgomery who had visited Palestine in June 1946 before taking up his post as Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Whitehall now ordered the High Commissioner and the 5,800 British police and 80,000 soldiers under his command to strike at the Jewish Agency and the Haganah. In the early hours of Saturday June 29th, 1946 - the Jewish Sabbath - 17,000 British troops launched 'Operation Agatha', occupying the Jewish Agency Building in Jerusalem and seizing documents whilst key members of its executive were detained. Armed with detailed intelligence, British soldiers scoured Tel-Aviv for hidden arms caches and, in the far-flung kibbutz settlements, they rounded up members of the Haganah's strike force, the Palmach. In forty-eight hours, 2,718 people had been arrested and, at one kibbutz alone, nearly 600 weapons, half a million rounds of ammunition and a quarter of a ton of explosives were unearthed.

Ben-Gurion escaped the British dragnet only because he was in Paris. Moshe Sneh, the Haganah commander, acting on a tip-off, also avoided arrest, but for the Jewish Agency and the Haganah, 'Operation Agatha', known locally as 'Black Saturday', constituted a severe blow. In retaliation for the raid on the Jewish Agency Building, Sneh planned something much more dramatic: an attack on the seat of British authority in Palestine, the King David Hotel. He was also convinced - mistakenly, as it turned out - that the documents which the British had removed from the Jewish Agency had been taken to the hotel where they might reveal evidence of collusion between the Jewish Agency and the 'dissidents'. The Haganah was too badly shaken up by 'Black Saturday' to mount such an operation, so on July 1st 1946, Moshe Sneh and his operations officer, Yitzhak Sadeh, approached the Irgun and Lehi for help. Begin agreed to do it, provided the attackers gave the people inside the King David, especially Jews working there, time to get clear. Anxious to ensure that the destruction of the captured Jewish Agency files occurred before they could be removed from the building, Sneh and Sadeh grudgingly allowed a thirty-minute warning.

Begin deputed twenty-six-year-old Amihai 'Gidi Paglin, his trusted operations officer and chief bomb maker, to plan and to organize the attack. Set for July 18th, 'Operation Malonchick' (Little House), as it was code-named, was the most ambitious Irgun operation to date. To lead it, 'Gidi' selected Yitzhak 'Gideon' Avinoam, the leader of the Irgun's Jerusalem cell. From his own ranks, 'Gideon' chose twenty male and female volunteers, whom he divided into three groups - 'assault', 'porters' and 'diversionary'. In the meantime, the Jewish Agency special operations liaison committee, which had originally approved the operation, now ordered Sneh to push it back to July 22nd. Chaim Weizmann was about to head off to London in an attempt to re-open negotiations with the British government, so any major operation by the United Jewish Resistance would wreck his mission. A little later, Moshe Sneh's deputy, Israel Galili, requested yet another postponement. This time, Begin - anxious to prevent any further delays alerting the British - ignored it. The attack on the King David was fixed for the morning of July 22nd allowing 'Gidi' just enough time to smuggle into Jerusalem the milk churns and high explosives needed for the operation.

The hotel occupied a four-and-a-half acre site overlooking Jerusalem's Old City on land purchased from the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate by a consortium headed by Azra Moseri, a wealthy Egyptian Jewish banker who owned Shepheard's Hotel in Cairo. Opened in December 1930, the massive six-storey building had been built to withstand earthquakes. It boasted 200 rooms with central heating, a tennis court, two restaurants, a banqueting hall, a luxuriously decorated grand lobby and a rose garden. As well as a traveller's rest for generals, statesmen, kings, maharajahs and princesses, the King David was also the hub of Jerusalem's cosmopolitan social scene. Growing up in a poor Jewish quarter in the city, Amos Oz remembered how his parents dreamed of belonging to this world of privilege and pleasure,

... where culture-seeking Jews and Arabs mixed with cultivated Englishmen with perfect manners, where dreamy, long-necked ladies floated in evening dresses, on the arms of gentlemen in dark suits, where there were recitals, balls, literary evenings, the dansants and exquisite, artistic conversations.

By 1946, the King David had lost much of its original lustre; sentry posts, thick coils of barbed wire and searchlights ringed the building and barriers bisected all the approach roads. Yet surprisingly, in view of the fact that it housed the British military and civilian headquarters for the whole of Palestine, it remained a functioning hotel. Dick Crossman wrote in his diary,

The atmosphere... is terrific, with private detectives, Zionist agents, Arab sheikhs, special correspondents, and the rest, all sitting about discreetly overhearing each other... The security precautions are very impressive... This morning, when I went out on to the terrace, I watched the sappers using their mine detectors to search the garden of the hotel.

The impression of vigilance was an illusion; 'Gideon's' team of bombers and gunmen was able to penetrate the King David's security cordon with ease. However, getting out of it proved problematic in more ways than one. Despite Begin's insistence on the thirty-minute fuses and the telephone warnings, ninety-one people had died, among them seventeen Jews, and the Irgun was now saddled with the blame for the huge death toll. In Paris, Ben-Gurion denounced it as an enemy of the Jewish people. It was pure hypocrisy: the attack on the King David Hotel had been ordered by the Haganah, which was ultimately answerable to Ben-Gurion. Sneh's requests to postpone the bombing, designed to spare Weizmann embarrassment during his mission to London, did not represent any fundamental disagreement between the Haganah and the Irgun over the efficacy of political violence, just the ability of the mainstream Zionist movement to choose between terrorism one moment and negotiation the next, whenever it suited. Compared to Ben-Gurion, Begin was an unsophisticated, naive idealist.

In August, the Haganah dissolved the United Jewish Resistance to devote its energies to defying the British ban on illegal Jewish immigration. Free of its control, the Irgun and Lehi continued their guerrilla war against the Mandate authorities. Sixteen months after the King David atrocity, the British - exasperated by their inability to suppress Jewish terrorism and anxious to limit the damage caused by their continued presence in Palestine - announced their decision to quit by mid-May 1948. On February 22nd that year, Arab terrorists took a leaf out of the Irgun's books by detonating three car bombs in Ben Yehuda Street in the heart of Jewish Jerusalem, killing fifty-two civilians and injuring hundreds more This constituted the opening salvo in a war of terror that persists to this very day.

On May 15th, 1948, David Ben-Gurion declared the establishment of the state of Israel, so fulfilling the main political objectives of not only the mainstream Zionist movement but also those of the Irgun and Lehi. Like the IRA throughout the twentieth century and Bin Laden today, Menachem Begin had 'adopted terrorism as a rational choice to bring certain political goals nearer and as a short-cut to transforming the political landscape'. With the realization of those goals, he had no further need of it. Much to the surprise of political opponents who regarded him as little better than a fascist thug, Begin became a model parliamentarian. In 1976, after the victory of his Likud Party in the polls, he became Israel's sixth prime minister; in 1983, he was succeeded by another ex-terrorist, the former Lehi fighter Yitzhak Shamir. Whether Bin Laden or any of his associates in al-Qaeda will survive long enough to make a similar transition from terrorist to statesman, only time will tell.

Revival of demolitions as terror deterrent sparks Israeli debate

The Israeli government's decision to demolish the homes of terrorists involved in the recent spate of terror attacks has been strongly criticised in the media.

Opinion on the policy is sharply divided in Israel, and it's true - as many journalists including the Australian Financial Review's Tony Walker here in Australia have noted - that in 2005, then-Chief of Staff (today Defence Minister) Moshe Ya'alon advised then-Defence Minister Shaul Mofaz to end the practice, after a committee established to evaluate the practice concluded that, in the words of Jerusalem Post reporter Margot Dudkevitch it "failed to serve as a deterrent."

However, what most international journalists, including Walker, have failed to mention is that the report was not terribly conclusive. The committee actually did find that it worked in some cases - though it was believed its effectiveness was cancelled out by the resentment the policy spawned among other Palestinians.

This was reflected in a statement issued by the IDF Spokesperson at the time that warned that "in the event of an extreme change in circumstances, the army would be free to reevaluate the policy" - suggesting that, like a tourniquet, the IDF believed it might have value as an emergency, temporary measure, especially against unplanned acts of terrorism.

As Dudkevitch wrote:

Opinion on the policy is sharply divided in Israel, and it's true - as many journalists including the Australian Financial Review's Tony Walker here in Australia have noted - that in 2005, then-Chief of Staff (today Defence Minister) Moshe Ya'alon advised then-Defence Minister Shaul Mofaz to end the practice, after a committee established to evaluate the practice concluded that, in the words of Jerusalem Post reporter Margot Dudkevitch it "failed to serve as a deterrent."

However, what most international journalists, including Walker, have failed to mention is that the report was not terribly conclusive. The committee actually did find that it worked in some cases - though it was believed its effectiveness was cancelled out by the resentment the policy spawned among other Palestinians.

This was reflected in a statement issued by the IDF Spokesperson at the time that warned that "in the event of an extreme change in circumstances, the army would be free to reevaluate the policy" - suggesting that, like a tourniquet, the IDF believed it might have value as an emergency, temporary measure, especially against unplanned acts of terrorism.

As Dudkevitch wrote:

"An IDF official said that while the practice had a deterrent effect in some cases, 'the IDF weighed whether the deterrent was strong enough to justify its continuation. And the chief of General Staff concluded that, especially when [the situation] is quiet, it's not time to use this policy.'"

In a story that appeared in the print edition of the Sydney Morning Herald on November 21, the New York Times' Jodi Rudoren presented a more nuanced and accurate picture of the uncertainty and ambivalence surrounding the policy in the Israeli government and security establishment.

"After halting the widespread practice of destroying homes in 2005, when a commission found that it rarely worked as a deterrent and instead inflamed hostility, Israel this northern summer also sealed or destroyed the homes of four Palestinians who had killed Jews, having previously done the same to two in 2009."

Unfortunately the SMH edited out from the NYT story a key quote from Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's Spokesperson Mark Regev. In the quote, Regev highlighted the impact of incitement and glorification of terror by the Palestinian leadership and the various financial and other incentives that encourage Palestinians to engage in terrorism.

Regev said:

"There is a culture of support within Palestinian society - these people are put up on a pedestal, they become martyrs, they become heroes, they are praised by the Palestinian leadership, their families are embraced, there are also very practical benefits for the family vis-a-vis financial support. In many ways, an action against the house is evening of the playing field. One is saying that by committing a heinous crime, in this case by murdering a baby, there will be a price to be paid."

The return of the policy comes at the recommendation of the Shin Bet over that of the IDF, according to reports by Israel Hayom's Nadav Shragai and Ynet's Nahum Barnea.

As Barnea explained:

"There is a dispute over the effectiveness of home demolitions: The Shin Bet says it has a deterring effect, while the IDF says it doesn't and could even achieve the opposite goal - sowing the seeds to the next attack. Each side presents data affirming its opinion, and there is no one to decide."

Moreover, housing demolitions have also been viewed as a method to offset the financial incentives provided to those who commit acts of terror, as Adam Chandler discussed in the Atlantic:

"While the policy is meant to have a psychological effect for a would-be attacker whose family would be left homeless, some suggest house demolitions are also designed to offset the economic benefits of committing an attack. One example: During the first three years of the Second Intifada, the families of Palestinian suicide bombers, as well as the families of those killed in clashes with Israel, routinely received checks for up to $25,000 from former Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein.

Hussein may be gone, but the financial incentives for Palestinian attackers who are jailed or killed are still around. Back in June, when Israel first announced it would resume house demolitions after three Israeli teenagers were kidnapped and killed, an Israeli official told the Jerusalem Post:

'On the Palestinian side you have a whole package of incentives to carry out terrorist attacks, such as if we arrest the terrorist, their families get a generous allowance from the PA.'"

The Netanyahu government has decided to stand by the policy, for now. The Israeli Foreign Ministry issued a backgrounderon the policy on November 19, denying it was a punitive action.

"The demolition of residences is not used as a punitive action. Rather, demolition is an act of deterrence, designed to discourage other terrorists and thereby minimize the number of future terrorist attacks. This measure is also undertaken in accordance with the rule of military necessity, so as to prevent terrorists from returning to their property and using it for further terrorist activities."

The briefing also explored the legality of the policy, and the safeguards and recourse available to those who would be affected by the policy.

"The demolition of a terrorist's house is a lawful administrative measure. However, Israel is aware of the serious potential effects of demolitions and therefore endeavors to minimize the use of this measure to the extent possible. Consequently, demolitions are carried out only in the most extreme circumstances.

The measure is only employed after high-ranking officials in the Ministry of Justice, security forces and the government approve its use. Moreover, as in all administrative measures, demolitions are conducted in accordance with the principles and rules of due process. Among the safeguards in place is the right of any person who might be potentially affected by the demolition to appeal directly to Israel's Supreme Court. The Supreme Court, sitting as a High Court of Justice, exercises full judicial review over demolitions."

Netanyahu has also stressed the intention of the demolition policy to be a deterrent, in conjunction with other steps, like stripping east Jerusalem terrorists of benefits that come with their permanent residency.

As Netanyahu said at the opening of the weekly cabinet meeting on Sunday:

As Netanyahu said at the opening of the weekly cabinet meeting on Sunday:

"Over the weekend I instructed Cabinet Secretary Avichai Mendelbit, along with Interior Minister Gilad Erdan, to submit draft legislation to revoke rights from residents who participate in terrorism or incitement against the State of Israel. It cannot be that those who attack Israeli citizens and call for the elimination of the State of Israel will enjoy rights such as National Insurance, and their family members as well, who support them. This law is important in order to exact a price from those who engage in attacks and incitement, including the throwing of stones and firebombs, and it complements the demolition of terrorists' homes, and helps to create deterrence vis-à-vis those who engage in attacks and incitement."

Commentary and analysis in the Israeli media has been lively and varied.

On the English-language radio station TLV1, Hilit Barel from the Council for Peace and Security and a former member of the National Security Council and Prof. Eugene Kontorovich, an international law expert from Northwestern University and senior fellow at the Kohelet Forum in Jerusalem, discussed the issue.

Ha'aretz predictably came out strongly against the return of a policy of demolitions, in an article that termed them "immoral" and "ineffective", yet even its journalist Asher Schechter could not claim to know for certain just how ineffective it ultimately is.

Schechter hedged:

On the English-language radio station TLV1, Hilit Barel from the Council for Peace and Security and a former member of the National Security Council and Prof. Eugene Kontorovich, an international law expert from Northwestern University and senior fellow at the Kohelet Forum in Jerusalem, discussed the issue.

Ha'aretz predictably came out strongly against the return of a policy of demolitions, in an article that termed them "immoral" and "ineffective", yet even its journalist Asher Schechter could not claim to know for certain just how ineffective it ultimately is.

Schechter hedged:

"One can claim, of course, that by demolishing homes Israel is in fact preventing many more terrorist attacks that would have taken place if it weren't for this deterrent. It's a legitimate claim. But by the same token, one also has to accept that it might have also provoked a few."

Schechter also pointed out - as only a handful of global journalists have done - that the origins of the policy aren't Israeli at all, rather they were first used by the British against militant Jews and Arabs during the Mandate period.

Ynet published an article by Israeli author Smadar Shir and columnist Merav Betito, with Shir supporting the measure and Betito arguing against.

Finally, also, at Ynet, columnist Rafael Castro argued that by authorising the demolishing of homes of terrorists from east Jerusalem, the government is actually weakening its claim over a united city of Jerusalem. Castro noted that the government did not demolish the homes of Jewish terrorists arrested several months ago for the revenge killing of an Arab teen from east Jerusalem, nor, he wrote, would they ever consider demolishing the home of an Israeli Arab from anywhere else in Israel regardless of their crime.

Most experts believe that the policy will be short-lived, one way or the other. Either calm will return, in which case there won't be any need to demolish terrorists' homes, or if it does not appear to have a significant effect on reducing attacks, it will be rescinded as ineffective.

Ynet published an article by Israeli author Smadar Shir and columnist Merav Betito, with Shir supporting the measure and Betito arguing against.

Finally, also, at Ynet, columnist Rafael Castro argued that by authorising the demolishing of homes of terrorists from east Jerusalem, the government is actually weakening its claim over a united city of Jerusalem. Castro noted that the government did not demolish the homes of Jewish terrorists arrested several months ago for the revenge killing of an Arab teen from east Jerusalem, nor, he wrote, would they ever consider demolishing the home of an Israeli Arab from anywhere else in Israel regardless of their crime.

Most experts believe that the policy will be short-lived, one way or the other. Either calm will return, in which case there won't be any need to demolish terrorists' homes, or if it does not appear to have a significant effect on reducing attacks, it will be rescinded as ineffective.

British fighting terror

ReplyDeleteHow the British Fought Arab Terror in Jenin and elsewhere in Palestine

"Demolishing the homes of Arab civilians…" "Shooting handcuffed prisoners…" "Forcing local Arabs to test areas where mines may have been planted…" These sound like the sort of accusations made by British and other European officials concerning Israel's recent actions in. In fact, they are descriptions from official British documents concerning the methods used by the British authorities to combat Palestinian Arab terrorism in Palestine and elsewhere in 1938.

The documents were declassified by London in 1989. They provide details of the British Mandatory government's response to the assassination of a British district commissioner by a Palestinian Arab terrorist in Jenin in the summer of 1938. Even after the suspected assassin was captured (and then shot dead while allegedly trying to escape), the British authorities decided that "a large portion of the town should be blown up" as punishment. On August 25 of that year, a British convoy brought 4,200 kilos of explosives to Jenin for that purpose. In the Jenin operation and on other occasions, local Arabs were forced to drive "mine-sweeping taxis" ahead of British vehicles in areas where Palestinian Arab terrorists were believed to have planted mines, in order "to reduce [British] land mine casualties." The British authorities frequently used these and similar methods to combat Palestinian Arab terrorism in the late 1930s. British forces responded to the presence of terrorists in the Arab village of Miar, north of Haifa, by blowing up house after house in October 1938. "When the troops left, there was little else remaining of the once busy village except a pile of mangled masonry," the New York Times reported.

The declassified documents refer to an incident in Jaffa in which a handcuffed prisoner was shot by the British police. Under Emergency Regulation 19b, the British Mandate government could demolish any house located in a village where terrorists resided, even if that particular house had no direct connection to terrorist activity. Mandate official Hugh Foot later recalled "When we thought that a village was harboring rebels, we would go there and mark one of the large houses. Then, if an incident was traced to that village, we would blow up the house we had marked." The High Commissioner for Palestine, Harold MacMichael, defended the practice "The provision is drastic, but the situation has demanded drastic powers."

MacMichael was furious over what he called the "grossly exaggerated accusations" that England's critics were circulating concerning British anti-terror tactics in Palestine. Arab allegations that British soldiers gouged out the eyes of Arab prisoners were quoted prominently in the Nazi German press and elsewhere.

The declassified documents also record discussions among officials of the Colonial Office concerning the anti-terror methods used in Palestine. Lord Dufferin remarked "British lives are being lost and I do not think that we, from the security of Whitehall, can protest squeamishly about measures taken by the men in the frontline." Sir John Shuckburgh defended the tactics on the grounds that the British were confronted "not with a chivalrous opponent playing the game according to the rules, but with gangsters and murderers."

There were many differences between British policy in the 1930's and Israeli policy today, but two stand out. The first is that the British, faced with a level of Palestinian Arab terrorism considerably less lethal than that which Israel faces today, nevertheless utilized anti-terror methods considerably harsher than those used by Israeli forces. The second is that when the situation became unbearable, the British could go home; the Israelis, by contrast, have no other place to go.