Israel Finally Officially Requesting Compensation for Jewish Refugees from Arab Countries!

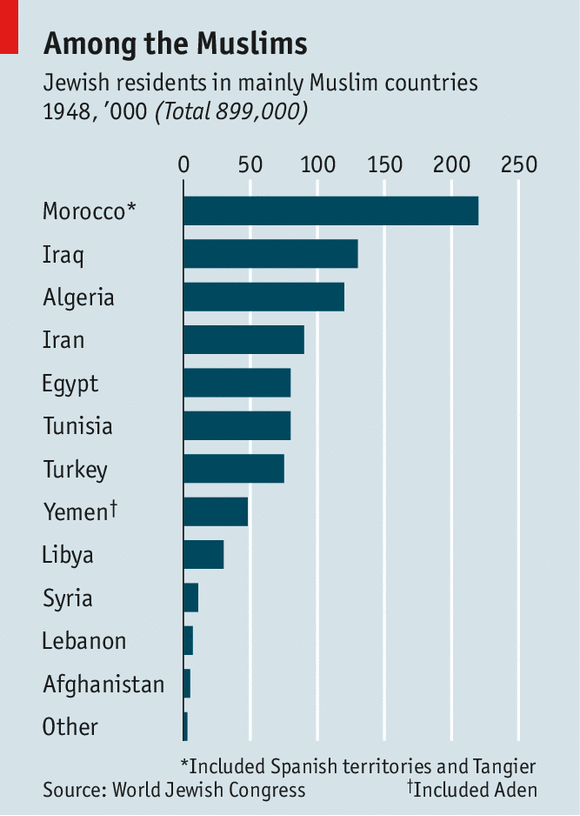

After decades of avoiding the issue the Israeli Foreign Ministry is finally placing this issue front and center for the international community to deal with in any context dealing with the “rights of refugees”, whether Arab or Jewish. 1 million Jewish refugees were created by the Arab/Muslim countries in the Middle East due to the establishment of the State of Israel. These refugees outnumber the Palestinian refugees two to one, but their narrative has all but been ignored. Finally, Israel is putting the issue on the international agenda!

The Arab media was up in arms this week over a plan spearheaded by Deputy Foreign Minister Danny Ayalon to hold a summit on the issue of Jewish refugees from Arab countries at the UN in September.

The summit’s main purpose is to push forward the matter of property rights of Jewish refugees who were forced to flee Arab countries after the establishment of the state of Israel and to turn the Jewish refugee issue into a bargaining chip which would make it clear that if the Palestinians voice demands for refugee compensation – demands would also be made from the Israeli side.

Watch The Movie: The Forgotten Refugees (about the forgotten Jewish refugees from Arab Countries)

Egypt’s press has recently shown a great deal of interest in the matter. Several papers have written that following the July 1971 revolution in the country, Jewish property devolved to state ownership under law. The press estimated the property to be worth 1 billion Egyptian Lira.

The local Egyptian press also noted that at the beginning of the 1950s there were some 100,000 Jews in Egypt of which only 25 remain in Egypt today. They are claiming that Israel is demanding the rights to some $21 billion worth of property in the old Jewish quarter of Cairo, including the large Adly Street Synagogue.

Egyptian media also quoted Israeli reports on the campaign. The Al Youm al-Saba newspaper carried the headline: “Israel enlisting the world to recognize Egyptian Jews and Jews from Arab countries as ‘refugees’.”

Jewish refugees from Arab lands

Don’t forget what we lost, too

Compensation for Jews pushed out of Arab lands may become yet another issue

MUCH as Palestinian refugees and their offspring remember the orange groves and cinemas they lost in Jaffa when Israel was born in 1948, Jews who once lived in Iraq recite the qasidas—lyrical Arabic poetry—and recall the time when most of Iraq’s banks and transport companies were run by Jews. “Iraq has gone downhill since they forced us out,” sighs a professor at a gathering of academics of Iraqi origin at Or Yehuda, a Tel Aviv suburb, slipping into Arabic. “Mubki, lamentable.”

American officials are unclear on the subject of whether they have formally raised the issue of Jews driven out of Arab lands as part of their proposed framework to establish an international fund to compensate Palestinians who fled the new state of Israel in 1948. But leaders of Israel’s Sephardic Jews (most of whom came from Arab lands) criticise their own negotiators for not raising the issue more forcefully.

“Why does Israel ask for compensation for Holocaust victims but not for the Jews from the Arab world?” asks Levana Zamir, leader of an association for Egyptian Jews in Israel. “Because our leaders are Ashkenazi [European Jews], and we are Mizrahim [Orientals],” she says. “We had another kind of Shoah [Holocaust]. A million Jews [from Arab lands] lost everything.”

Tzipi Livni, Israel’s chief negotiator, an Ashkenazi, fears that adding such topics could complicate to distraction efforts to resolve matters arising from Israel’s occupation of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank after the six-day Arab-Israeli war of 1967. For some Israelis, that may be just the idea. Binyamin Netanyahu, Israel’s prime minister, has repeatedly raised the issue, apparently to offset any claims for compensation from the Palestinians uprooted in 1948, 750,000 of whom fled abroad and 150,000 of whom were displaced within what became Israel. Mr Netanyahu’s ministry for senior citizens has opened a hotline for claimants to register lost property in the Arab and Muslim world (including Turkey and Iran), which, campaigners argue, will exceed the price-tag of between $20 billion and $100 billion which Israeli officials privately put on Palestinian claims.

Palestinians are as sceptical as Ms Livni about recognising a Jewishnakba (or catastrophe, the word Palestinians use to describe what happened in 1948). It would merely add more knots, they say, to the tangle of negotiations. In any event, Israel’s Zionist leaders promoted the idea of Jews finding their real home, thus never considering them refugees. To bolster their fledgling state, they sent agents from Mossad, their foreign intelligence service, to “ingather” Jews with airlifts from the Arab world. Fearing another post-war slaughter, Zionist spokesmen campaigned for “their quick transfer…to the new Jewish state”, as the New York Times reported at the time.

Despite the complications, though, a compensation scheme for Israel’s Mizrahim could give the negotiations a political boost. Making up an estimated 55% of Israeli Jews, Mizrahim have tended to vote for right-wing parties loth to cut a deal that would bring about a Palestinian state, partly because they still harbour grievances over their own dispossession after 1948. Turning them into stakeholders could raise the number of Israelis voting for a settlement in a referendum. “Of course, we would support it, if our rights are recognised,” says Shmuel Moreh, an Iraqi-born professor of Arabic literature at Israel’s Hebrew University, who forsook his Baghdad home laden with silver chandeliers for a tent in Or Yehuda, when the suburb was just a muddy camp for Jewish exiles.

Compensation for Jewish as well as Arab victims of Israel’s creation could also help pave a way to Israel’s normalisation with the Arab world, says Ehud Eiran, an Israeli academic, just as Germany’s compensation scheme for Holocaust victims improved Israel’s relations with Europe.

No comments:

Post a Comment