Today in Zionist History: The San Remo Conference

Salomon Benzimra, co-founder of Canadians for Israel’s Legal Rights, explains the rights of the Jewish State to the entire Land of Israel according to international law, based on the San Remo Conference of 1920.

Salomon Benzimra, co-founder of Canadians for Israel’s Legal Rights, explains the full legal rights of the Jewish State to the Land of Israel based on the San Remo Conference of 1920.

The Middle East keeps making the headlines. The carnage in Syria, the weekly violence in Iraq, the political instability in Lebanon, the uncertainty in Turkey, the threat posed by Iran in the Region – all seem to take a backseat to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the perennial pursuit of peace. US Secretary of State John Kerry’s initiative was the most recent of many failed attempts since 1993.

When the search for a resolution of a complex problem –almost predictably and repeatedly since its inception – hits a stalemate, the smart thing to do is to revisit the fundamentals, in this case long forgotten in the past 20 years of diplomatic frenzy. A look back at recent history is essential.

Jewish National Home Determined by San Remo Conference

(1920)

Pre-1948 Maps: Table of Contents | Roman Empire (500) | Hebron (1912)

|

San Remo Conference Drafted Map of the Middle East

Ninety-four years ago today, on April 25, 1920, the Supreme Council of the Allied Powers (Britain, France, Italy, Japan and the US as an observer) gathered in San Remo, Italy, and ruled on the disposition of the Middle East territories previously held by the defeated Ottoman Empire. They first listened to the claims of both the Zionist Organization [later renamed the World Zionist Organization], headed by Chaim Weizmann, and the Arab Delegation, headed by Emir Faisal, at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919.

After the San Remo Conference, the Jewish National Home unquestionably included all the territory west of the Jordan River.

The San Remo Conference was a momentous event in that it drafted the map of the Middle East as we know it today: Over 97% of the land was adjudicated to the Arabs, which resulted in the creation of the new, exclusively Arab states of Syria, Lebanon, Iraq and, later, Jordan. The geographic region known as Palestine was designated as the Jewish National Home, to be reconstituted there in consideration of the historical connection of the Jewish people to the land.

National rights were exclusively granted to the Jewish people collectively, while the non-Jewish people of Palestine were granted individual civil and religious rights.

These were the terms used in the San Remo Resolution, which were later confirmed in the Mandate for Palestine (1922) and approved by the 52 members of the League of Nations in order to highlight the preexisting rights of the Jewish people to the Land of Israel, hitherto known as Palestine since Roman times. These documents, and the ensuing Franco-British and Anglo-American treaties that were separately signed in the early 1920s, are based on the Mandates System stipulated in the Covenant of the League of Nations and are therefore binding to this day under international law.

The acquired rights of the Jewish people to the land west of the Jordan River are preserved in the UN Charter and in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, even though the Mandate for Palestine expired in 1948 when the State of Israel was proclaimed.

The usual detractors of Israel regularly ignore, dismiss or strongly reject the validity of the provisions listed above. But their arguments ring hollow.

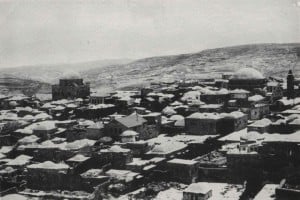

Jewish Quarter in east Jerusalem, 1898. (Encyclopedia of Israel in Pictures, published 1952)

They claim that the Supreme Council of the Allied Powers had no authority to create a new political entity in Palestine. They forget that in the wake of World War One, the same Supreme Council created new countries in Europe (Yugoslavia, Hungary, the Baltic States and a reborn Poland) on the ashes of the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires.

They also claim that a Jewish home in Palestine was not intended to include all of Palestine. Had they read the full text of the Mandate for Palestine, they would find 15 instances of the phrase “in Palestine” – which leaves no doubt as to the inclusion of the entire territory.

San Remo Conference Settled Territorial Claims

These same detractors claim that the purpose of the “Jewish National Home” mentioned in the Mandate was not meant to lead to a sovereign Jewish state. Here again, they are most selective in their singling out of Israel; not only were all the neighboring Arab states created through the same Mandates System, but Mandated territories in far less developed areas in Africa and elsewhere also became sovereign states in the second half of the 20th century. Cameroon, Togo, Benin, Rwanda, Burundi, Tanzania, Namibia, Papua New Guinea and Samoa are a few examples.

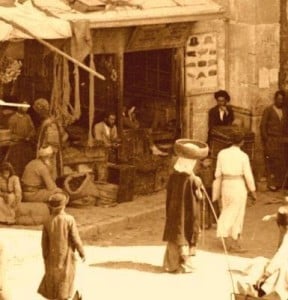

Jewish millinery shop in east Jerusalem, 1898. (American Colony, Photo Dept.)

What happened 90 Years Ago in San Remo Italy?

Although quite unknown to most, San Remo, Italy was the place where, in “modern times”, it was decided that Israel would be the official internationally recognized homeland of the Jewish people.

It was about 90 years ago when the original dividing of the Middle Eastern lands took place in this quaint Italian town called San Remo, and still today many are unfamiliar with its history. Watch this fascinating video to become educated about the internationally recognized rights of the Jewish People to the Land of Israel.

It was about 90 years ago when the original dividing of the Middle Eastern lands took place in this quaint Italian town called San Remo, and still today many are unfamiliar with its history. Watch this fascinating video to become educated about the internationally recognized rights of the Jewish People to the Land of Israel.

You are guaranteed to learn something you didn’t know. Most importantly, we ask you to SHARE this very important video with everyone you know!

Thursday, January 30, 2014

San Remo's Mandate: Israel's 'Magna Carta'

Monday, April 25, 2011

JERUSALEM, Israel - This year marks the 91st anniversary of the resolution that transformed the Middle East and laid the groundwork for the formation of the modern state of Israel.

On April 25, 1920, delegations from the Allied nations that triumphed in World War I met in San Remo, Italy, to divide the Middle Eastern lands they had conquered.

That historical meeting transformed the Middle East because, for the first time in nearly 2,000 years, the world's nations called for the establishment of a Jewish homeland in the land that was then called Palestine.

That decision effectively answered a fundamental issue that still plagues the Israeli-Palestinian peace talks today: whether Israel is an occupying power or it has a rightful claim to the land.

Watch Gordon Robertson give a biblical perspective on Israel's claim to the land, following Chris Mitchell's report.

Dividing an Empire

In San Remo - England, France, Italy, and Japan, with the United States as an observer, divided the Ottoman Empire empire into three mandates: Iraq, Syria and Palestine.

Until its defeat in World War 1, the 400-year-old empire had spread itself throughout the Middle East. Now, France would oversee Syria, while Iraq and Palestine fell under Great Britain.

The resolution also included the Balfour Declaration, written by England's Lord Balfour in 1917. The declaration called for "the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people." One British diplomat, Lord Curzon, called it Israel's "Magna Carta."

Arab's Lion-Share, Israel's Niche

Last year, on the 90th anniversary of the signing of the San Remo resolution, Tomas Sandell of the European Coalition of Israel helped organize an historic gathering.

Click here to watch expanded interviews and more with participants from this historic event commemorating the signing of the San Remo resolution.

"Chaim Weizman said, at the time, you can say that the Israeli state was born on the 25th of April in San Remo because that was the significance of it," Sandell said.

Howard Grief said the resolution, which was adopted by the League of Nations, established several important precedents.

In his book, The Legal Foundation and Borders of Israel under International Law, Grief explains that the resolution gave the Jewish people exclusive legal and political rights in Palestine. It also gave the Arabs the same rights for the remainder of the Middle East.

"The Arabs got the lion's share….I mean they got Syria, which was subsequently divided between Syria and Lebanon," Grief said.

"They got all of Mesopotamia and all of Arabia. This is what Balfour himself said. 'Why are you complaining? You are getting all these lands and we're granting a niche - he called it a niche - to the Jewish people who were going to get Palestine," he said.

Immutable Law

Grief also explained that the 1920 San Remo resolution supersedes later U.N. resolutions.

"There is a doctrine in international law," Grief said. "Once you recognize a certain situation, the matter is executed. You can't change it."

"The U.N. General Assembly exceeded its authority, exceeded its jurisdiction. It did not have the power to divide the country," he said.

Settling Contested 'Settlements'

But what about all those contested Israeli "settlements" in Judea and Samaria (the West Bank) that many people - including U.N. Secretary-general Ban Ki-moon - say are illegal?

"Settlements are covered in Article 6 of the mandate for Palestine," Eli Hertz, president of Myths and Facts, explained to conference participants.

"Again the legal international document of the mandate for Palestine and [it] clearly says that not only [do] the Jews have the right to settlement, but the world has the obligation to help them to settle," Hertz explained.

This legal right of the Jews to build in Judea and Samaria or in east Jerusalem neighborhoods is little understood in the world today.

Sandell said he hopes to remedy that problem.

"We feel that we have an historical duty to just bring the facts to the table," Sandell said. "Because we are here dealing with historical facts and this should be known and this should be taken into consideration in the public debate."

Watch expanded interviews with some of the participants in this historic event commemorating the 90th anniversary of the San Remo resolution:

- Tomas Sandell, the founding director of the European Coalition for Israel, helped organize the 90th anniversary event. ECI seeks to education European leaders "about the complex realities of the conflict in the Middle East by acknowledging the right for Israel, as the only democracy in the region, to exist within secure borders." Click here for more from Sandell.

- Eli Hertz is the president of Myths and Facts, a research organization focused much on the Middle East. Hertz has written a short pamphlet on this subject called "This Land is My Land: Mandate for Palestine, Legal Aspects of Jewish Rights," an excellent primer and succinct explanation of the legal foundation of the Jewish state. Click here for more from Hertz.

- Salomon Benzimra is from Canadians for Israel's Legal Rights. Benzimra and Goldie Steiner of CILR played a pivotal role in organizing the anniversary. CILR believes "... that a just peace in the Middle-East cannot be achieved while crucial facts are ignored, hidden or distorted." Click here for more from Benzimra.

- Danny Danon is the only member of Knesset from Israel to attend the anniversary of the signing of the San Remo Resolution. Click here to watch his message to a seminar the day before the anniversary.

--Originally aired July 11, 2010.

THE SAN REMO CONFEERENCE IN CONTEXT

It is impossible to understand the complex legal implications of the Arab-Israel conflict without an acquaintance with the basics of following context.

THE SAN REMO CONFERENCE

in relation to

McMAHON, SYKES-PICOT, THE BALFOUR DECLARATION, AND THE BRITISH MANDATE

in relation to

McMAHON, SYKES-PICOT, THE BALFOUR DECLARATION, AND THE BRITISH MANDATE

Article 6 of the Mandate, charged Britain with the duty to facilitate Jewish immigration and close settlement by Jews in the territory which then included Transjordan, as called for in the Balfour declaration, that had already been adopted by the other Allied Powers. As a trustee, Britain had a fiduciary duty to act in good faith in carrying out the duties imposed by the Mandate.Furthermore, as the San Remo resolution has never been abrogated, it was and continues to be legally binding between the several parties who signed it.It is therefore obvious that the legitimacy of Syria, Lebanon, Iraq and the Jewish state all derive from the same international agreement at San Remo.

The 1915 McMahon-Hussein Agreement

In 1915 Sir Henry McMahon made promises on behalf of the British government, via Sherif Hussein of Mecca, about allocation of territory to the Arab people. Although Hussein understood from the promises that Palestine would be given to the Arabs, the British later claimed that land definitions were only approximate and that a map drawn at the time excluded Palestine from territory to be given to the Arab people. However in a subsequent change of policy in recognition of the McMahon correspondence, and in violation of its mandate, Britain separated the territory east of the Jordan River namely Transjordan (since renamed Jordan) from Palestine west of the Jordan.In his book “State and economics in the Middle East: a society in transition” (Routledge, 2003), Alfred Bonné included a letter from Sir Henry McMahon to The Times of London dated July 23,1937 in which he wrote, “I feel it my duty to state, and I do so definitely and emphatically, that it was not intended by me in giving this pledge to King Hussein to include Palestine in the area in which Arab independence was promised. I also had every reason to believe at the time that the fact that Palestine was not included in my pledge was well understood by King Hussein.”Bonné considered the letter to be of such importance that he published it in full as copied below

The May 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement

This secret agreement between Britain, France and Russia was concluded by British diplomat, Sir Mark Sykes and French diplomat Georges Picot. In seeking to divide the entire Middle East into areas of influence for each of the imperial powers but leaving the Holy Lands to be jointly administered by the three powers, it clashed materially with the McMahon Agreement. It was intended to hand Syria, Mesopotamia, Lebanon and Cilicia (in south-eastern Asia Minor) to the French and Palestine, Jordan and areas around the Persian Gulf and Baghdad including Arabia and the Jordan Valley to the British.Although intended to be secret, the Arabs learned about the agreement from communists who found a copy in the Russian government’s archives.

The 1917 Balfour Declaration

he Balfour Declaration is contained in the following letter from Lord Arthur Balfour, the British foreign secretary, to Lord Rothschild, president of the British Zionist Federation,Foreign OfficeNovember 2nd, 1917

Dear Lord Rothschild,

I have much pleasure in conveying to you, on behalf of His Majesty’s Government, the following declaration of sympathy with Jewish Zionist aspirations which has been submitted to, and approved by, the Cabinet.

“His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

I should be grateful if you would bring this declaration to the knowledge of the Zionist Federation.

Yours sincerely,

Arthur James Balfour

Arthur James Balfour

The declaration was accepted by the League of Nations on July 24, 1922 and embodied in the mandate that gave Great Britain administrative control of Palestine as d escribbed in more detail below.

THE SAN REMO CONFERENCE 1920

After ruling vast areas of Eastern Europe, South-western Asia, and North Africa for centuries, the Ottoman Empire lost all its Middle East territories during World War One. The Treaty of Sèvres of August 10, 1920 abolished the Ottoman Empire and obliged Turkey to renounce all rights over Arab Asia and North Africa. It was replaced by the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923.The status of the Ottoman Empire’s former possessions was determined at a conference in San Remo, Italy on April 24-25, 1920 attended by Great Britain, France, Italy, Japan and as an observer, the United States. Syria and Lebanon were mandated to France while Mesopotamia (Iraq) and the southern portion of the territory (Palestine) were mandated to Britain, with the charge to implement the Balfour Declaration.While the Balfour Declaration was in itself not a legally enforceable document, it did become legally enforceable by being entrenched in international law when it was incorporated in its entirety in a resolution passed by the Conference on April 25. Significantly, the only change made to the wording of the Balfour Declaration was to strengthen Britain’s obligation to implement the Balfour Declaration. Lord Curzon described the San Remo resolution as “the Magna Carta of the Zionists”.

Though borders were not yet precisely defined, the conference gave Palestine a legal identity. Lloyd George, the British Prime Minister at the time used the expression “from Dan to Beersheba” that was often used in subsequent documents.

The conference’s decisions were confirmed unanimously by all fifty-one member countries of the League of Nations on July 24, 1922 and they were further endorsed by a joint resolution of the United States Congress in the same year,

The San Remo resolution received a further US endorsement in the Anglo-American Treaty on Palestine, signed by the US and Britain on December 3, 1924, that incorporated the text of the Mandate for Palestine. The treaty protected the rights of Americans living in Palestine under the Mandate and more significantly it also made those rights and provisions part of United States treaty law which are protected under the US constitution. The U.S. Senate ratified the treaty on February 20, 1925 followed by President Calvin Coolidge on March 2, 1925 and by Great Britain on March 18, 1925.

Britain was specifically charged with giving effect to the establishment of the Jewish National Home in Palestine that was called for in the Balfour declaration that had already been adopted by the other Allied Powers. It is therefore obvious that the legitimacy of Syria, Lebanon, Iraq and a Jewish state in Palestine as defined before the creation of Transjordan, all derive from the same binding international agreement at San Remo, that has never been abrogated.

Commemoration of the San Remo conference

In April 2010, a ceremony attended by politicians and others from Europe, the U.S. and Canada was held in San Remo at the house where the signing of the San Remo declaration took place in 1920. At the conclusion of the commemoration, the following statement was released:”Reaffirming the importance of the San Remo Resolution of April 25, 1920 – which included the Balfour Declaration in its entirety – in shaping the map of the modern Middle East, as agreed upon by the Supreme Council of the Principal Allied Powers (Britain, France, Italy, Japan, and the United States acting as an observer), and later approved unanimously by the League of Nations; the Resolution remains irrevocable, legally binding and valid to this day.”Emphasizing that the San Remo Resolution of 1920 recognized the exclusive national Jewish rights to the Land of Israel under international law, on the strength of the historical connection of the Jewish people to the territory previously known as Palestine.

“Recalling that such a seminal event as the San Remo Conference of 1920 has been forgotten or ignored by the community of nations, and that the rights it conferred upon the Jewish people have been unlawfully dismissed, curtailed and denied.

“Asserting that a just and lasting peace, leading to the acceptance of secure and recognized borders between all States in the region, can only be achieved by recognizing the long established rights of the Jewish people under international law.”

As stated above, the San Remo Conference decided to place Palestine under British Mandatory rule making Britain responsible for giving effect to the Balfour declaration that had been adopted by the other Allied Powers. The resulting “Mandate for Palestine,” was an historical League of Nations document that laid down the Jewish legal right to settle anywhere in Palestine and the San Remo Resolution together with Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations became the basic documents on which the Mandate for Palestine was established.The Mandate’s declaration of July 24, 1922 states unambiguously that Britain became responsible for putting the Balfour Declaration, in favor of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, into effect and it confirmed that recognition had thereby been given to the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine and to the grounds for reconstituting their national home in that country.It is highly relevant that at that time the West Bank and parts of what today is Jordan were included as a Jewish Homeland. However, on September 16, 1922, the British divided the Mandate territory into Palestine, west of the Jordan and Transjordan, east of the Jordan River, in accordance with the McMahon Correspondence of 1915. Transjordan became exempt from the Mandate provisions concerning the Jewish National Home, effectively removing about 78% of the original territory of the area in which a Jewish National home was to be established in terms of the Balfour Declaration and the San Remo resolution as well as the British Mandate.

This action violated not only Article 5 of the Mandate which required the Mandatory to be responsible for seeing that no Palestine territory shall be ceded or leased to, or in any way placed under the control of the Government of any foreign Power but also article 20 of the Covenant of the League of Nations in which the Members of the League solemnly undertook that they would not enter into any engagements inconsistent with the terms thereof.

Article 6 of the Mandate stated that the Administration of Palestine, while ensuring that the rights and position of other sections of the population are not prejudiced, shall facilitate Jewish immigration under suitable conditions and shall encourage, in co-operation with the Jewish agency referred to in Article 4, close settlement by Jews on the land, including State lands and waste lands not required for public purposes.

Nevertheless in blatant violation of article 6, in a 1939 White Paper Britain changed its position so as to limit Jewish immigration from Europe, a move that was regarded by Zionists as betrayal of the terms of the mandate, especially in light of the increasing persecution of Jews in Europe. In response, Zionists organized Aliyah Bet, a program of illegal immigration into Palestine.

CONCLUSION

The frequently voiced complaint that the state being offered to the Palestinians comprises only 22 percent of Palestine is obviously invalid. The truth is exactly the reverse. From the above history it is obvious that the territory on both sides of the Jordan was legally designated for the Jewish homeland by the 1920 San Remo Conference, mandated to Britain, endorsed by the League of Nations in 1922, affirmed in the Anglo-American Convention on Palestine in 1925 and confirmed in 1945 by article 80 of the UN. Yet, approximately 80% of this territory was excised from the territory in May 1923 when, in violation of the mandate and the San Remo resolution, Britain gave autonomy to Transjordan (now known as Jordan) under as-Sharif Abdullah bin al-Husayn.Furthermore, as the San Remo resolution has never been abrogated, it was and continues to be legally binding between the several parties who signed it.It is therefore obvious that the legitimacy of Syria, Lebanon, Iraq and a Jewish state in Palestine all derive from the same international agreement at San Remo.

In essence, when Israel entered the West Bank and Jerusalem in 1967 it did not occupy territory to which any other party had title. While Jerusalem and the West Bank, (Judea and Samaria), were illegally occupied by Jordan in 1948 they remained in effect part of the Jewish National Home that had been created at San Remo and in the 1967 6-Day War Israel, in effect, recovered territory that legally belonged to it. To quote Judge Schwebel, a former President of the ICJ, “As between Israel, acting defensively in 1948 and 1967, on the one hand, and her Arab neighbors, acting aggressively, in 1948 and 1967, on the other, Israel has the better title in the territory of what was Palestine, including the whole of Jerusalem.

Selected Writings of Stephen M. Schwebel, Judge of International Court of Justice

(not written in any of his former official capacities)

Justice In International Law

07/06/09

Judge Schwebel has served on the Court since 15 January 1981. He was Vice-President of the Court from 1994 to 1997 and has been President since 6 February 1997. A former Deputy Legal Adviser of the United States Department of State and Burling Professor of International Law at the School of Advanced International Studies of The John Hopkins University (Washington), Judge Schwebel is the author of three books and some 150 articles on problems of international law and organization.

Judge Schwebel has served on the Court since 15 January 1981. He was Vice-President of the Court from 1994 to 1997 and has been President since 6 February 1997. A former Deputy Legal Adviser of the United States Department of State and Burling Professor of International Law at the School of Advanced International Studies of The John Hopkins University (Washington), Judge Schwebel is the author of three books and some 150 articles on problems of international law and organization.

What Weight to Conquest?

AGGRESSION, COMPLIANCE, AND DEVELOPMENT

AGGRESSION, COMPLIANCE, AND DEVELOPMENT

Pages 521-526

In his admirable address of December 9, 1969, on the situation in the Middle East, Secretary of State William P. Rogers took two positions of particular international legal interest, one implicit and the other explicit. (1) Secretary Rogers called upon the Arab States and Israel to establish “a state of peace … instead of the state of belligerency, which has characterized relations for over 20 years.” Applying this and other elements of the American approach to the United Arab Republic and Israel, the Secretary of State suggested that, “in the context of peace and agreement [between the UAR and Israel] on specific security safeguards, withdrawal of Israeli forces from Egyptian territory would be required.” (2)

Secretary Rogers accordingly inferred that, in the absence of such peace and agreement, withdrawal of Israeli forces from Egyptian territory would not be required. That is to say, he appeared to uphold the legality of continued Israeli occupation of Arab territory pending “the establishment of a state of peace between the parties instead of the state of belligerency.” (3) In this Secretary Rogers is on sound ground. That ground may well be based on appreciation of the fact that Israel’s action in 1967 was defensive, and on the theory that, since the danger in response to which defensive action was taken remains, occupation – though not annexation – is justified, pending a peace settlement. But Mr. Rogers’s conclusion may be simply a pragmatic judgment (indeed, certain other Permanent Members of the Security Council, which are not likely to share the foregoing legal perception, are not now pressing for Israeli withdrawal except as an element of a settlement).

More questionable, however, is the Secretary of State’s explicit conclusion on a key question of the law and politics of the Middle East dispute: that “any changes in the pre-existing [1949 armistice] lines should not reflect the weight of conquest and should be confined to insubstantial alterations required for mutual security. We do not support expansionism.” Secretary Rogers referred approvingly in this regard to the Security Council’s resolution of November 1967, which,

Emphasizing the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by war (4) and the need to work for a just and lasting peace in which every State in the area can live in security,

Emphasizing further that all Member States in their acceptance of the Charter of the United Nations have undertaken a commitment to act in accordance with Article 2 of the Charter,

1. Affirms that the fulfillment of Charter principles requires the establishment of a just and lasting peace in the Middle East which should include the application of both the following principles:

(i) Withdrawal of Israeli armed forces from territories occupied in the recent conflict; (5)

(ii) Termination of all claims or states of belligerency and respect for and acknowledgement of the sovereignty, territorial integrity and political independence of every State in the area and their right to live in peace within secure and recognized boundaries free from threats or acts of force; …” (6)

It is submitted that the Secretary’s conclusion is open to question on two grounds: first, that it fails to distinguish between aggressive conquest and defensive conquest; second, that it fails to distinguish between the taking of territory which the prior holder held lawfully and that which it held unlawfully. These contentions share common ground.

As a general principle of international law, as that law has been reformed since the League, particularly by the Charter, it is both vital and correct to say that there shall be no weight to conquest, that the acquisition of territory by war is inadmissible. (7) But that principle must be read in particular cases together with other general principles, among them the still more general principle of which it is an application, namely, that no legal right shall spring from a wrong, and the Charter principle that the Members of the United Nations shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any State. So read, the distinctions between aggressive conquest and defensive conquest, between the taking of territory legally held and the taking of territory illegally held, become no less vital and correct than the central principle itself.

Those distinctions may be summarized as follows: (a) a State acting in lawful exercise of its right of self-defense may seize and occupy foreign territory as long as such seizure and occupation are necessary to its self defense; (b) as a condition of its withdrawal from such territory, that State may require the institution of security measures reasonably designed to ensure that that territory shall not again be used to mount a threat or use of force against it of such a nature as to justify exercise of self-defense; (c) where the prior holder of territory had seized that territory unlawfully, the State which subsequently takes that territory in the lawful exercise of self-defense has, against that prior holder, better title.

The facts of the June 1967 “Six Day War” demonstrate that Israel reacted defensively against the threat and use of force against her by her Arab neighbors. This is indicated by the fact that Israel responded to Egypt’s prior closure of the Straits of Tiran, its proclamation of a blockade of the Israeli port of Eilat, and the manifest threat of the UAR’s use of force inherent in its massing of troops in Sinai, coupled with its ejection of UNEF. It is indicated by the fact that, upon Israeli responsive action against the UAR, Jordan initiated hostilities against Israel. It is suggested as well by the fact that, despite the most intense efforts by the Arab States and their supporters, led by the Premier of the Soviet Union, to gain condemnation of Israel as an aggressor by the hospitable organs of the United Nations, those efforts were decisively defeated. The conclusion to which these facts lead is that the Israeli conquest of Arab and Arab-held territory was defensive rather than aggressive conquest.

The facts of the 1948 hostilities between the Arab invaders of Palestine and the nascent State of Israel further demonstrate that Egypt’s seizure of the Gaza Strip, and Jordan’s seizure and subsequent annexation of the West Bank and the old city of Jerusalem, were unlawful. Israel was proclaimed to be an independent State within the boundaries allotted to her by the General Assembly’s partition resolution. The Arabs of Palestine and of neighboring Arab States rejected that resolution. But that rejection was no warrant for the invasion by those Arab States of Palestine, whether of territory allotted to Israel, to the projected, stillborn Arab State or to the projected, internationalized city of Jerusalem. It was no warrant for attack by the armed forces of neighboring Arab States upon the Jews of Palestine, whether they resided within or without Israel. But that attack did justify Israeli defensive measures, both within and, as necessary, without the boundaries allotted her by the partition plan (as in the new city of Jerusalem). It follows that the Egyptian occupation of Gaza, and the Jordanian annexation of the West Bank and Jerusalem, could not vest in Egypt and Jordan lawful, indefinite control, whether as occupying Power or sovereign: ex injuria jus non oritur.

If the foregoing conclusions that (a) Israeli action in 1967 was defensive and (b) Arab action in 1948, being aggressive, was inadequate to legalize Egyptian and Jordanian taking of Palestinian territory, are correct, what follows?

It follows that the application of the doctrine of according no weight to conquest requires modification in double measure. In the first place, having regard to the consideration that, as between Israel, acting defensively in 1948 and 1967, on the one hand, and her Arab neighbors, acting aggressively in 1948 and 1967, on the other, Israel has better title in the territory of what was Palestine, including the whole of Jerusalem, than do Jordan and Egypt (the UAR indeed has, unlike Jordan, not asserted sovereign title), it follows that modifications of the 1949 armistice lines among those States within former Palestinian territory are lawful (if not necessarily desirable), whether those modifications are, in Secretary Rogers’s words, “insubstantial alterations required for mutual security” or more substantial alterations – such as recognition of Israeli sovereignty over the whole of Jerusalem. (8) In the second place, as regards territory bordering Palestine, and under unquestioned Arab sovereignty in 1949 and thereafter, such as Sinai and the Golan Heights, it follows not that no weight shall be given to conquest, but that such weight shall be given to defensive action as is reasonably required to ensure that such Arab territory will not again be used for aggressive purposes against Israel. For example – and this appears to be envisaged both by the Secretary of State’s address and the resolution of the Security Council – free navigation through the Straits of Tiran shall be effectively guaranteed and demilitarized zones shall be established.

The foregoing analysis accords not only with the terms of the United Nations Charter, notably Article 2, paragraph 4, and Article 51, but law and practice as they have developed since the Charter’s conclusion. In point of practice, it is instructive to recall that the Republic of Korea and indeed the United Nations itself have given considerable weight to conquest in Korea, to the extent of that substantial territory north of the 38th parallel from which the aggressor was driven and remains excluded – a territory which, if the full will of the United Nations had prevailed, would have been much larger (indeed, perhaps the whole of North Korea). In point of law, provisions of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties are pertinent. Article 52 provides that: “A treaty is void if its conclusion has been procured by the threat or use of force in violation of the principles of international law embodied in the Charter of the United Nations” – a provision which clearly does not debar conclusion of a treaty where force has been applied, as in self-defense, in accordance with the Charter. And Article 75 provides that: “The provisions of the present Convention are without prejudice to any obligation in relation to a treaty which may arise for an aggressor State in consequence of measures taken in conformity with the Charter of the United Nations with reference to that State’s aggression.”

The state of the law has been correctly summarized by Elihu Lauterpacht, who points out that

territorial change cannot properly take place as a result of the unlawful use of force. But to omit the word “unlawful” is to change the substantive content of the rule and to turn an important safeguard of legal principle into an aggressor’s charter. For if force can never be used to effect lawful territory change, then, if territory has once changed hands as a result of the unlawful use of force, the illegitimacy of the position thus established is sterilized by the prohibition upon the use of force to restore the lawful sovereign. This cannot be regarded as reasonable or correct. (9)

© Judge Stephen Myron Schwebel *

Notes

First published in American Journal of International Law (1970), 64

(1) The text is published in full in New York Times, December 11, 1969, p. 16.

(2) Ibid.

(3) Ibid

(4) The resolution’s use of the word “war” is of interest. The June 1967 hostilities were not marked by a declaration of war. Certain Arab States have regarded themselves at war with Israel – or, at any rate, in a state of belligerency – since 1948, a questionable position under the law of the Charter. In view of the defeat in the United Nations organs of resolutions holding Israel to have been the aggressor in 1967, presumably the use of the word “war” was not meant to indicate that Israel’s action was not in exercise of self-defense. It may be added that territory would not in any event be acquired by war, but, if at all, by the force of treaties of peace.

(5) It should be noted that the resolution does not specify “all territories” or “the territories” but “territories.” The subparagraph immediately following is, by way of contrast, more comprehensively cast, specifying “all claims or states of belligerency.”

(6) Resolution 242 (1967) of November 22, 1967; 62 AJIL 482 (1968). President Johnson, in an address of September 10, 1968, declared:

We are not the ones to say where other nations should draw the lines between them that will assure each the greatest security. It is clear, however, that a return to the situation of June 4, 1967, will not bring peace. There must be secure and there must be recognized borders …

At the same time, it should be equally clear that boundaries cannot and should not reflect the weight of conquest. Each change must have a reason which each side, in honest negotiation, can accept as part of a just compromise. (59 Department of State Bulletin 348 [1968])

(7) See, however, Kelsen (2nd ed. by Tucker), Principles of International Law (1967), pp. 420-433.

(8) It should be added that the armistice agreements of 1949 expressly preserved the territorial claims of all parties and did not purport to establish definitive boundaries between them.

(9) Elihu Lauterpacht, Jerusalem and the Holy Places, Anglo-Israel Association, Pamphlet No. 19 (1968), p. 52.

* Since 1947 Stephen M. Schwebel has written more than 100 articles, commentaries and book reviews in legal and other periodicals and in the press. This volume republishes 36 of his legal articles and commentaries of continuing interest. The first Part treats aspects of the capacity and performance of the International Court of Justice. The second addresses aspects of international arbitration. The third examines problems of the United Nations, especially of the authority of the Secretary-General, the character of the Secretariat, and financial apportionment. The fourth deals with questions of international contracts and taking of foreign property interests. The fifth discusses diverse aspects of the development of international law and particularly considers the central problem of international law, the unlawful use of force. This collection does not include Judge Schwebel’s judicial opinions, nor (with one exception) papers written in his former official capacities as a legal officer of the US Department of State or as a special rapporteur of the International Law Commission of the United Nations. Together with his unofficial writings, his judicial opinions as of July 1993 are cataloged in the list of publications with which this volume concludes.

Justice in international law: selected writings of Judge Stephen M. Schwebel

Par Stephen Myron Schwebel

Édition: illustrée

Publié par Cambridge University Press, 1994

ISBN 0521462843, 9780521462846

630 pages

EXTRACTS

That ground may well be based on appreciation of the fact that Israel’s action in 1967 was defensive, and on the theory that, since the danger in response to which defensive action was taken remains, occupation – though not annexation – is justified, pending a peace settlement

Those distinctions may be summarized as follows:

(a) a State acting in lawful exercise of its right of self-defense may seize and occupy foreign territory as long as such seizure and occupation are necessary to its self-defense;

(a) a State acting in lawful exercise of its right of self-defense may seize and occupy foreign territory as long as such seizure and occupation are necessary to its self-defense;

(b) as a condition of its withdrawal from such territory, that State may require the institution of security measures reasonably designed to ensure that that territory shall not again be used to mount a threat or use of force against it of such a nature as to justify exercise of self-defense;

(c) where the prior holder of territory had seized that territory unlawfully, the State which subsequently takes that territory in the lawful exercise of self-defense has, against that prior holder, better title.

The facts of the June 1967 “Six Day War” demonstrate that Israel reacted defensively against the threat and use of force against her by her Arab neighbors. This is indicated by the fact that Israel responded to Egypt’s prior closure of the Straits of Tiran, its proclamation of a blockade of the Israeli port of Eilat, and the manifest threat of the UAR’s use of force inherent in its massing of troops in Sinai, coupled with its ejection of UNEF. It is indicated by the fact that, upon Israeli responsive action against the UAR, Jordan initiated hostilities against Israel. It is suggested as well by the fact that, despite the most intense efforts by the Arab States and their supporters, led by the Premier of the Soviet Union, to gain condemnation of Israel as an aggressor by the hospitable organs of the United Nations, those efforts were decisively defeated. The conclusion to which these facts lead is that the Israeli conquest of Arab and Arab-held territory was defensive rather than aggressive conquest.

…it follows that modifications of the 1949 armistice lines among those States within former Palestinian territory are lawful (if not necessarily desirable), whether those modifications are, in Secretary Rogers’s words, “insubstantial alterations required for mutual security” or more substantial alterations – such as recognition of Israeli sovereignty over the whole of Jerusalem.[8]…..

In point of practice, it is instructive to recall that the Republic of Korea and indeed the United Nations itself have given considerable weight to conquest in Korea, to the extent of that substantial territory north of the 38th parallel from which the aggressor was driven and remains excluded – a territory which, if the full will of the United Nations had prevailed, would have been much larger (indeed, perhaps the whole of North Korea)..

..The state of the law has been correctly summarized by Elihu Lauterpacht, who points out that

..if force can never be used to effect lawful territory change, then, if territory has once changed hands as a result of the unlawful use of force, the illegitimacy of the position thus established is sterilized by the prohibition upon the use of force to restore the lawful sovereign. This cannot be regarded as reasonable or correct.[9]

NOTE re the 1949 armistice lines

Secretary of State Rogers, December 9, 1969

The boundaries from which the 1967 war began were established in the 1949 Armistice Agreements and have defined the areas of national jurisdiction in the Middle East for 20 years. Those boundaries were armistice lines, not final political borders. The rights, claims and positions of the parties in an ultimate peaceful settlement were reserved by the Armistice Agreements.

Statement by Secretary of State Rogers, 9 December 1969:

By the end of 1969, the Jarring Mission has reached an impasse. The Arab States would not negotiate with Israel directly or indirectly. There was heavy fighting along the Suez Canal. Palestinian terrorists were engaged in sabotage actions against Israel from Jordan and Syria, assisted by the armed forces of those two countries. Prime Minister Golda Meir visited the United States in late September 1969, and met with President Nixon in Washington on 25 and 26 September. While no formal announcement was made, it was assumed that a good understanding had been reached. But, on 9 December, Secretary of State Rogers, addressing an Adult Education Conference in Washington, made a number of proposals for a Middle East settlement, going into details on the future borders of Israel and other issues. The section dealing with the Middle East follows:

Following the third Arab-Israeli war in twenty years, there was an upsurge of hope that a lasting peace could be achieved. That hope has unfortunately not been realized. There is no area of the world today that is more important, because it could easily again be the source of another serious conflagration.

When this Administration took office, one of our first actions in foreign affairs was to examine carefully the entire situation in the Middle East. It was obvious that a continuation of the unresolved conflict there would be extremely dangerous; that the parties to the conflict alone would not be able to overcome their legacy of suspicion to achieve a political settlement; and that international efforts to help needed support.

The United States decided it had a responsibility to play a direct role in seeking a solution.

Thus, we accepted a suggestion put forward both by the French Government and the Secretary-General of the United Nations. We agreed that the major Powers - the United States, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and France - should cooperate to assist the Secretary-General's representative, Ambassador Jarring, in working out a settlement in accordance with the Resolution of the Security Council of the United Nations of November 1967. We also decided to consult directly with the Soviet Union, hoping to achieve as wide an area of agreement as possible between us.

These decisions were made in full recognition of the following important factors.

First, we knew that nations not directly involved could not make a durable peace for the peoples and Governments involved. Peace rests with the parties to the conflict. The efforts of major Powers can help; they can provide a catalyst; they can help define a realistic framework for agreement; but an agreement among other Powers cannot be a substitute for agreement among the parties themselves.

Second, we knew that a durable peace must meet the legitimate concerns of both sides.

Third, we were clear that the only framework for a negotiated settlement was one in accordance with the entire text of the UN Security Council Resolution. That Resolution was agreed upon after long and arduous negotiations; it is carefully balanced; it provides the basis for a just and lasting peace - a final settlement - not merely an interlude between wars.

Fourth, we believed that a protracted period of war, no peace, recurrent violence and spreading chaos would serve the interests of no nation, in or out of the Middle East.

For eight months we have pursued these consultations, in Four Power talks at the United Nations, and in bilateral discussions with the Soviet Union.

In our talks with the Soviets, we have proceeded in the belief that the stakes are so high that we have a responsibility to determine whether we can achieve parallel views which would encourage the parties to work out a stable and equitable solution. We are under no illusions, we are fully conscious of past difficulties and present realities. Our talks with the Soviets have brought a measure of understanding, but very substantial differences remain. We regret that the Soviets have delayed in responding to new formulations submitted to them on 28 October. However, we will continue to discuss these problems with the Soviet Union as long as there is any realistic hope that such discussion might further the cause of peace.

The substance of the talks that we have had with the Soviet Union have been conveyed to the interested parties through diplomatic channels. This process has served to highlight the main roadblocks to the initiation of useful negotiations among the parties.

On the one hand, the Arab leaders fear that Israel is not in fact prepared to withdraw from Arab territory occupied in the 1967 war.

Now on the other hand, Israeli leaders fear that the Arab States are not in fact prepared to live in peace with Israel.

Each side can cite from its viewpoint considerable evidence to support its fears. Each side has permitted its attention to be focused solidly and to some extent solely on these fears.

What can the United States do to help overcome these roadblocks?

Our policy is and will continue to be a balanced one.

We have friendly ties with both Arabs and Israelis. To call for Israeli withdrawal as envisaged in the UN Resolution without achieving an agreement on peace would be partisan towards the Arabs. To call on the Arabs to accept peace without Israeli withdrawal would be partisan towards Israel. Therefore, our policy is to encourage the Arabs to accept a permanent peace based on a binding agreement and to urge the Israelis to withdraw from occupied territory when their territorial integrity is assured as envisaged by the Security Council Resolution.

In an effort to broaden the scope of discussion, we have recently resumed Four Power negotiations at the United Nations.

Let me outline our policy on various elements of the Security Council Resolution. The basic and related issues might be described as peace, security, withdrawal and territory. Peace between the parties: - the Resolution of the Security Council makes clear that the goal is the establishment of a state of peace between the parties instead of the state of belligerency which has characterized relations for over 20 years. We believe that the conditions and obligations of peace must be defined in specific terms. For example, navigation rights in the Suez Canal and in the Straits of Tiran should be spelled out. Respect for sovereignty and obligations of the parties to each other must be made specific.

But peace, of course, involves much more than this. It is also a matter of the attitudes and intentions of the parties. Are they ready to co-exist with one another? Can a live-and-let-live attitude replace suspicion, mistrust and hate? A peace agreement between the parties must be based on clear and stated intentions and a willingness to bring about basic changes in the attitudes and conditions which are characteristic of the Middle East today.

Security: - a lasting peace must be sustained by a sense of security on both sides. To this end, as envisaged in the Security Council Resolution, there should be demilitarized zones and related security arrangements more reliable than those which existed in the area in the past. The parties themselves, with Ambassador Jarring's help, are in the best position to work out the nature and the details of such security arrangements. It is, after all, their interests which are at stake and their territory which is involved. They must live with the results.

Withdrawal and territory: - the Security Council Resolution endorses the principle of the non-acquisition of territory by war and calls for withdrawal of Israeli armed forces from territories occupied in the 1967 war. We support this part of the Resolution, including withdrawal, just as we do its other elements.

The boundaries from which the 1967 war began were established in the 1949 Armistice Agreements and have defined the areas of national jurisdiction in the Middle East for 20 years. Those boundaries were armistice lines, not final political borders. The rights, claims and positions of the parties in an ultimate peaceful settlement were reserved by the Armistice Agreements.

The Security Council Resolution neither endorses nor-precludes these armistice lines as the definitive political boundaries. However, it calls for withdrawal from occupied territories, the non-acquisition of territory by war, and for the establishment of secure and recognized boundaries.

We believe that while recognized political boundaries must be established, and agreed upon by the parties, any change in the pre-existing lines should not reflect the weight of conquest and should be confined to insubstantial alterations required for mutual security. We do not support expansionism. We believe troops must be withdrawn as the Resolution provides. We support Israel's security and the security of the Arab States as well. We are for a lasting peace that requires security for both.

By emphasizing the key issues of peace, security, withdrawal and territory, I do not want to leave the impression that other issues are not equally important. Two in particular deserve special mention - the questions of refugees and of Jerusalem.

There can be no lasting peace without a just settlement of the problem of those Palestinians whom the wars of 1948 and 1967 made homeless. This human dimension of the Arab-Israeli conflict has been of special concern to the United States for over 20 years. During this period, the United States has contributed about 500 million dollars for the support and education of the Palestine refugees. We are prepared to contribute generously, along with others, to solve this problem. We believe its just settlement must take into account the desires and aspirations of the refugees and the legitimate concerns of the Governments in the area.

The problem posed by the refugees will become increasingly serious if their future is not resolved. There is a new consciousness among the young Palestinians who have grown up since 1948, which needs to be channelled away from bitterness and frustration towards hope and justice.

The question of the future status of Jerusalem, because it touches deep emotional, historical and religious well-springs, is particularly complicated. We have made clear repeatedly in the past two and a half years that we cannot accept unilateral actions by any party to decide the final status of the city. We believe its status can be determined only through the agreement of the parties concerned, which in practical terms means primarily the Governments of Israel and Jordan, taking into account the interests of other countries in the area and the international community. We do, however, support certain principles which we believe would provide an equitable framework for a Jerusalem settlement.

Specifically, we believe Jerusalem should be a unified city within which there would no longer be restrictions on the movement of persons and goods. There should be open access to the unified city for persons of all faiths and nationalities. Arrangements for the administration of the unified city should take into account the interests of all its inhabitants and of the Jewish, Islamic and Christian communities. And there should be roles for both Israel and Jordan in the civic, economic and religious life of the City.

It is our hope that agreement on the key issues of peace, security, withdrawal and territory will create a climate in which these questions of refugees and of Jerusalem, as well as other aspects of the conflict, can be resolved as part of the overall settlement.

During the first weeks of the current United Nations Gerneral Assembly, the efforts to move matters towards a settlement entered a particularly intensive phase. Those efforts continue today.

I have already referred to our talks with the Soviet Union. In connection with those talks there have been allegations that we have been seeking to divide the Arab States by urging the UAR to make a separate peace. These allegations are false. It is a fact that we and the Soviets have been concentrating on the questions of a settlement between Israel and the United Arab Republic. We have been doing this in the full understanding on both our parts that, before there can be a settlement of the ArabIsraeli conflict, there must be agreement between the parties on other aspects of the settlement - not only those related to the United Arab Republic but also those related to Jordan and other States which accept the Security Council Resolution of November 1967.

We started with the Israeli-United Arab Republic aspect because of its inherent importance for future stability in the area and because one must start somewhere.

We are also ready to pursue the Jordanian aspects of a settlement - in fact the Four Powers in New York have begun such discussions. Let me make it perfectly clear that the US position is that implementation of the overall settlement would begin only after complete agreement had been reached on related aspects of the problem.

In our recent meetings with the Soviets, we have discussed some new formulas in an attempt to find common positions. They consist of three principal elements:

First, there should be a binding commitment by Israel and the United Arab Republic to peace with each other, with all the specific obligations of peace spelled out, including the obligation to prevent hostile acts originating from their respective territories.

Second, the detailed provisions of peace relating to security safeguards on the ground should be worked out between the parties, under Ambassador Jarring's auspices, utilizing the procedures followed in negotiating the Armistice Agreements under Ralph Bunche in 1949 at Rhodes. His formula has been previously used with success in negotiations between the parties on Middle Eastern problems. A principal objective of the Four Power talks, we believe, should be to help Ambassador Jarring engage the parties in a negotiating process under the Rhodes formula.

So far as a settlement between Israel and the United Arab Republic goes, these safeguards relate primarily to the area of Sharm el-Sheikh controlling access to the Gulf of Aqaba, the need for demilitarized zones as foreseen in the Security Council Resolution, and final arrangements in the Gaza Strip.

Third, in the context of peace and agreement on specific security safeguards, withdrawal of Israeli forces from Egyptian territory would be required.

Such an approach directly addresses the principal national concerns of both Israel and the UAR. It would require the UAR to agree to a binding and specific commitment to peace. It would require withdrawal of Israeli armed forces from UAR territory to the international border between Israel and Egypt which has been in existence for over half a century. It would also require the parties themselves to negotiate the practical security arrangements to safeguard the peace.

We believe that this approach is balanced and fair.

We remain interested in good relations with all States in the area. Whenever and wherever Arab States which have broken off diplomatic relations with the United States are prepared to restore them, we shall respond in the same spirit.

Meanwhile, we will not be deterred from continuing to pursue the paths of patient diplomacy in our search for peace in the Middle East. We will not shrink from advocating necessary compromises, even though they may and probably will be unpalatable to both sides. We remain prepared to work with others - in the area and throughout the world - so long as they sincerely seek the end we seek: a just and lasting peace.

INTERNATIONAL LAW

The occupation, settlements and the Arab-Israel conflict

Click on the relevant link below for content

INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE ARAB-ISRAEL CONFLICT by Ian Lacey, B.A., LL.B

Extracts from “Israel and Palestine – Assault on the Law of Nations” by Professor Julius Stone

Extracts from “Israel and Palestine – Assault on the Law of Nations” by Professor Julius Stone

Inrernational Law and the settlements – an overviewThe Legalities in a nutshell – Including extracts from the above “INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE ARAB-ISRAEL CONFLICT” by Ian Lacey, B.A., LL.B.

Articles by Eugene RostowExtracts from the writings of Justice SchwebelYitxchak Rabin on Israel’s future borders. Remarks in his last speech

International law relating to occupation and settlementsThe occupation in perspectiveOccupied territories around the worldDisputed territories around the world

International law and warfare

International Law and the Fighting in Gaza by WEINER AND BELL © 2008 Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs

.

But among all Israel’s detractors, the Palestinian Authority has demonstrated a particular animosity towards San Remo. A document issued on April 25, 2011, by WAFA, the official press agency of the Palestinian Authority, claims that “[San Remo] is the root of all Palestinian catastrophes and sufferings,” and it bashes the San Remo Resolution as the work of “Zionist gangs.”

Now is the time to give precedence to factual evidence over biased opinion. On this 94th anniversary, we should remember that territorial claims on Palestine were finally settled at the San Remo Conference.

***Authoritative experts who have declared Israel’s presence in the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Golan to be legal, include inter alia

ReplyDelete• Judge Schwebel, a former President of the ICJ, who pronounced “As between Israel, acting defensively in 1948 and 1967, on the one hand, and her Arab neighbors, acting aggressively, in 1948 and 1967, on the other, Israel has the better title in the territory of what was Palestine, including the whole of Jerusalem.” (See Appendix A and http://www.2nd-thoughts.org/id248.html )

• Professor Julius Stone, one of the twentieth century’s leading authorities on the Law of Nations. See http://www.2nd-thoughts.org/id160.html

• Eugene W. Rostow, US Undersecretary of State for Political Affairs between 1966 and 1969 who played a leading role in producing the famous Resolution 242.

See http://www.2nd-thoughts.org/id45.html

• Jacques Gauthier, a non-Jewish Canadian lawyer who spent 20 years researching the legal status of Jerusalem leading to the conclusion on purely legal grounds, ignoring religious claims that Jerusalem belongs to the Jews, by international law. See http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=28qwcVPNy3E

and http://www.israelnationalnews.com/News/News.aspx/125049…

• William M. Brinton, who appealed against a US district court’s withholding of State Department documents concerning US policy on issues involving Israel and the West Bank, the Golan Heights, and the Gaza Strip. He showed that none of these areas fall within the definition of “occupied territories” and that any claim that the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, or both, is a Palestinian homeland to which the Palestinians have a ‘legitimate right’ lacks substance and does not survive legal analysis. According to Mr. Brinton no state, other than Israel, can show a better title to the West Bank.

• Sir Elihu Lauterpacht CBE QC., the British specialist in international law, who concludes inter alia that sovereignty over Jerusalem already vested in Israel when the 1947 partition proposals were rejected and aborted by Arab armed aggression.

• Simon H. Rifkind, Judge of the United States District Court, New York who wrote an in depth analysis “The basic equities of the Palestine problem” (Ayer Publishing, 1977) that was signed by Jerome N. Frank, Judge of the United States Circuit Court of Appeals Second Circuit; Stanley H. Fuld, Judge of the Court of Appeals of the State of New York; Abrahan Tulin, member of the New York Bar; Milton Handler, Professor of law, Columbia University; Murray L. Gurfein, member of the New York Bar; Abe Fortas, former Undersecretary of Interior of the United States and Lawrence R. Eno, member of the New York Bar. They jointly stated that justice and equity are on the side of the Jews in this document that they described as set out in the form of a lawyer’s brief.